Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Labor of Love

As Brandeis University nears its 75th anniversary, Jules Bernstein ’57 reflects on his alma mater’s beginnings, and his own, in "Overruled, Mr. Bernstein! Sometimes Down, But Never Out," a new collection of personal essays.

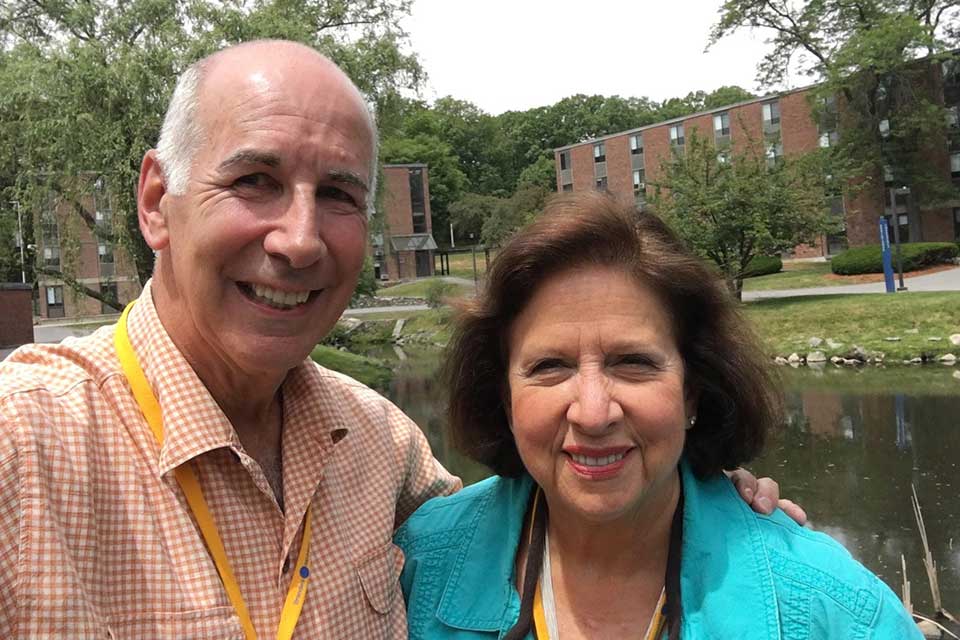

Meantime, the long-serving worker and union-side labor lawyer has capped off a lifetime of altruism by making, with his wife and law partner Lindsa Lipsett, a substantial bequest to Brandeis to endow the Louis D. Brandeis Legacy Fund for Social Justice. Bernstein established the fund at the university in 2006, and now serves as chair of its advisory committee, alongside Walt Mossberg ’69; Nancy Shapiro ’69; Shaina (Gilbert) Jean-Pierre ’10; Sahar Massachi ’11; Ajai Scott ’15, MA’19, MBA’19; and Elena Lewis.

Photo Credit: Stacey Rupolo

Bernstein has been an outspoken and proactive alumnus since graduating from Brandeis during its foundational years. Soon after his Commencement, the sixth in the university's short history, he wrote to Brandeis leadership to let them know what he admired most about his alma mater: “A commitment to truth (‘tell it like it is’) and social justice (‘make it like it oughta be!’).”

Bernstein has expressed his appreciation in equally direct and heartfelt ways ever since, with extraordinary generosity as both a participant and a donor. He has served on the Brandeis Board of Fellows; the Alumni Association Board of Directors; and the advisory boards of the Ethics Center, the Heller School, the Transitional Year Program, Posse, and the National Center for Jewish Film. He has supported summer social justice internships for students, and coordinated numberous reunions for the Class of 1957, including serving on his 50th Reunion committee in 2007. In addition, he started the A. Philip Randolph Fellowship for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion to honor the prominent 20th-century civil rights leader in 2007. Originally funding Posse scholarships, it now supports the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Scholarship in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Ensuring 'Life-Lasting' Impact

To date, Bernstein and Lipsett have made significant contributions to the Legacy Fund. Their current bequest is intended to endow the fund's Social Justice Internship Program in perpetuity. They want to ensure that the Legacy Fund will continue to enable students to pursue meaningful summer internship experiences in the social justice sector. Of such internships, Bernstein has said:

“The impact of experiential learning is life-lasting. For the most part, younger people are trying to look to their futures and are working on creating their lives and themselves. The lessons of experiential learning are important building blocks in this process. For older folks, we have a different task. We often spend our time looking back at our lives, trying to understand what happened, and trying to make sense and find meaning in our experiences. This requires honesty, courage, and insight. Experiential learning is an essential element of lifetime learning and must be respected and supported as such. It may serve as the source of insights and perceptions not previously imagined.” — Jules Bernstein ’57

Bernstein’s other contributions to Brandeis include the lead gift that created a scholarship in memory of Tony Williams, the Transitional Year Program’s founding director, and longtime support of ‘deisIMPACT!, Brandeis’ annual festival of social justice. In addition, Bernstein created the Louis D. Brandeis 150th Jubilee Fund, supporting programs and media in celebration of the 150th birthday of Louis Brandeis, including supporting “Louis Brandeis: The People’s Attorney,” a documentary directed by Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Charles Stuart, which aired on PBS.

Also, in 2007, Bernstein produced “Guided by the Light of Reason,” an award-winning scrapbook-style biography of Louis D. Brandeis; a copy is given to every incoming Brandeis student. Bernstein thought that such a publication was needed because there was no available summary of Justice Brandeis' life for Brandeis students and others.

“Jules is one of Brandeis’ most dedicated community members,” says President Ron Liebowitz. “Through his extraordinary giving and service, Jules has elevated our standard of alumni engagement. He continues to inspire many members of our university community through his work, and we are fortunate to benefit from his long-term commitment to his alma mater.”

In 2007, Bernstein received the Brandeis Alumni Achievement Award, the highest form of university recognition bestowed exclusively on alumni.

With Bernstein’s inspired, lifelong support of social justice, it is no surprise that he has been a labor lawyer advocating for workers’ rights since the 1960s. Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, he earned his bachelor’s in sociology at Brandeis, his doctor of jurisprudence from the University of Chicago Law School, and his master’s in labor law from the New York University Law School.

Bernstein and Lipsett have been practicing law together for over 40 years, specializing in Fair Labor Standards Act litigation and representing thousands of federal and other employees who have been the victims of "wage theft" by their employers.

Bernstein’s latest achievement is a collection of his articles and lectures on labor, politics, and personal experiences entitled, “Overruled, Mr. Bernstein! Sometimes Down, but Never Out.” Published in 2022, it addresses subjects including his Brandeis beginnings, labor economics, racism, and the Trump presidency, its aftermath, and the 2020-2022 pandemic.

In the first of our two-part series, we present an excerpt from Bernstein's new book that focuses on his life leading up to and during his years at Brandeis, which he fondly calls “academic utopia.”

About the Author

Annie is senior development writer in advancement communications. Before joining Brandeis in January 2022, she was a writer at Dartmouth College. As a longtime freelance journalist and radio commentator, she has covered art, culture, travel, and education for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, Art in America, Art New England, NPR, and many other outlets. She is the lucky mom of two great kids.

‘My Academic Elysium’: A Look Back at My Brandeis Beginnings

By Jules Bernstein ’57

When I was a high school student in the early 1950s, the New York Post was my political North Star. It was then owned by Dorothy Schiff, the granddaughter of Jacob Schiff, a German-born Jewish businessman and philanthropist. Hard as it is to fathom today, with the Post now part of Rupert Murdoch’s right-wing media empire, the paper was then a liberal daily led by its crusading editor, James Wechsler. Its two other stalwart left-wing commentators were Max Lerner and Murray Kempton.

As a youth, I had read Lerner in [the ultraliberal New York newspapers of the 1940s], following him from the PM to the short-lived New York Star, and then to the Post. There, along with the work of Wechsler and Kempton, I received a good part of my early political education. Several times each week, this “troika” would pen political columns on the events of the day. I read their commentaries religiously, as they provided a compelling counterpoint to a political climate dominated by McCarthyism, political witch hunts, and anti-communist hysteria while the Korean War raged.

Lerner wrote frequently about Brandeis University, where he had been teaching since 1949. It sounded to me, as a left-wing Brooklyn teenager, like an academic Elysium.

A World-Class University Is Born

Brandeis University was founded in the landmark year of 1948 (when the state of Israel was established and I became a bar mitzvah) by a group of Jewish businessmen-philanthropists from Boston and New York, most of whom had never attended college. Albert Einstein also was involved at the outset. They shared a vision of establishing a Jewish-sponsored, nonsectarian university. While many religious denominations had established colleges and universities in the United States, including Harvard, the University of Chicago, Wesleyan, Middlebury, Haverford, Georgetown, and scores of others, the American Jewish community had not followed suit, and a sentiment existed that it had a moral and patriotic duty to do so. Establishing a Jewish-sponsored university also reflected a Jewish concern that Jews had long been deliberately excluded from leading colleges and universities in the United States.

The university was named after Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1856–1941), who was born to an Austro-Hungarian immigrant Jewish family in Louisville, Kentucky, and had been an influential public interest lawyer in Boston as well as a leading Zionist. He was appointed to the United States Supreme Court by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, and he served until he retired in 1939.

Today, Justice Brandeis is widely recognized as one of the most distinguished jurists in American history, along with his colleague and friend, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Justice Brandeis is also viewed by many as the most outstanding Jew in American history. He was the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, followed in time by Benjamin Cardozo, Felix Frankfurter, Arthur J. Goldberg, Abe Fortas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Elena Kagan. Brandeis’ confirmation hearings in the United States Senate were controversial because of his trust-busting activities and his Jewish identity. President Wilson was required to make extraordinary personal efforts to assure his confirmation.

One of his many famous accomplishments as a lawyer was the so-called “Brandeis brief,” which sought to incorporate social and economic facts and considerations into the resolution of legal disputes, a novel idea at the time (1908). Indeed, it was a “Brandeis brief ” filed by the NAACP that played a major role in the ground-breaking 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, which declared racially separate public schools unconstitutional and reversed earlier decisions that had held otherwise.

A life-size statue of Louis D. Brandeis by sculptor Robert Berks was dedicated on the Brandeis campus in 1956 as part of the Justice Brandeis centennial celebration at the university. I attended the dedication ceremony, which featured a speech by then Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren.

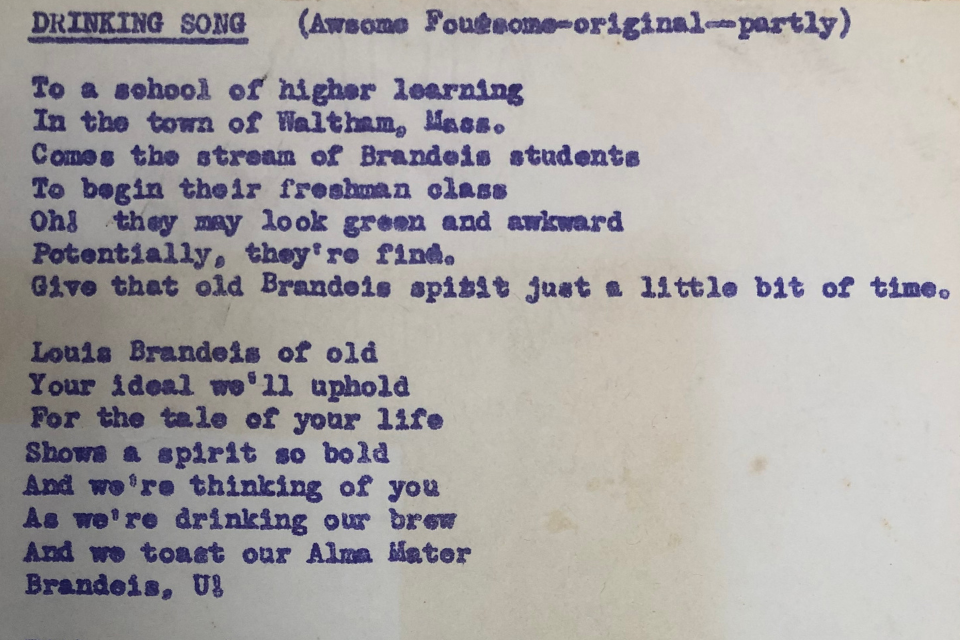

One of the drinking songs that my classmates and I frequently sang together reflects our allegiance to Justice Brandeis. It went:

Louis Brandeis of old, Your ideals we’ll uphold,

For the tale of your life Shows a spirit so bold,

And we’re thinking of you, As we’re drinking our brew,

As we toast our alma mater, Brandeis U.

Brandeis opened its doors to its first freshman class in September 1948. It was composed largely of a feisty and adventurous group of young Boston and New York Jews. Some were late-returning World War II veterans, attending college under the G.I. Bill of Rights, which included college tuition paid for by the federal government.

Initially, the school was very small, with fewer than 150 students and 15 faculty members. Though its beginning was not auspicious, Brandeis has evolved over [nearly 75 years] to be a major center of research and higher learning, with over 3,500 undergraduate students, 2,000 graduate students, and a large and prestigious faculty.

Before Brandeis

Having my interests awakened by Max Lerner’s columns about Brandeis, and with the encouragement from some of my high school teachers and my parents, I decided to apply there. While my grades were fairly mediocre, except in English and social studies, my position as editor of [my high school newspaper] helped. I recall my interview in 1952 at the Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan with a young Brandeis admissions officer named Phil Driscoll.

Presumably my grades, extracurricular activities, as well as my interview were sufficient to result in my admission for the term beginning September 1953. When my Brandeis acceptance letter arrived in the mail, it seemed the greatest day of my life to that point. It felt almost better than the Dodgers winning the pennant in 1947, in Jackie Robinson’s freshman year in the majors.

This was a new school whose future, and accreditation, were far from assured, so its applicant pool must have been small. Also, since I was a “Depression baby,” I was competing with a limited number of contemporaries and peers.

And So It Begins: My Life at Brandeis

As I did from 1951 through 1956, I spent the summer before college working as a waiter in the Poconos. Then I returned home and packed, and my parents drove me to Brandeis for freshman orientation week. I had never seen the Brandeis campus before, and though had been away from home every summer since 1947, I really did not know what to expect. However, I recall my confidence level as being fairly high. Frankly, I doubt that my parents had ever stepped foot on a college campus before, so this brief visit was new to them, too.

When I enrolled at Brandeis, the student body consisted of about 800 students. Most were Jewish (about 75-80 percent) and from either the Boston or New York metropolitan areas. By the time of my enrollment in September 1953, Brandeis had already held two graduations, the Classes of 1952 and 1953, and its third class of students (those who had entered in September 1950) would complete their degrees in June 1954. So my class of 1957 would be the sixth to graduate.

I was assigned to a dorm called Ridgewood A, which resembled a grouping of two-story garden apartments or a motel on a hillside at the edge of campus. It still stands today, although it has been enlarged and renovated. My room was on the second floor, a double that I shared with my roommate, Sam Coleman, a Black student from Waterbury, Connecticut. Of the 16 or so residents, about six were freshmen, and the others were upperclassmen. The dorm was all-male, and indeed, women students could not enter. They lived in the Castle and in Smith Hall.

On my first day at Brandeis, one of the dorm’s upperclassmen, Mark Samuels, volunteered to take several freshmen on a campus tour. What I remember is him pointing to a student who had just walked by and saying to us in hushed, reverential tones, “That’s Mike Walzer,” as if he were Mahatma Gandhi. I brashly asked whether Walzer was the quarterback of the Brandeis football team that was then in training for the fall season. Mark explained that Walzer was not the quarterback but rather a leading student intellectual, loved and trusted by all, who as a freshman during the preceding year had received straight As. “He’s our leader,” Mark said.

Mike Walzer and I became friends and comrades at Brandeis. He married a member of my class, Judy Borodovko, and went on, after teaching at Harvard, to an appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, where Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppeheimer had done much of their work. He has been there since 1980 and has written many books, most in philosophy and politics.

My Brandeis freshman class of close to three hundred students had a few days of orientation with faculty, staff, and students, and we then dove into our studies. We ate three meals a day together on campus in the cafeteria in the Castle, talking, discussing, gossiping, and always learning. And was there a lot to learn!

This is an excerpt from “Overruled, Mr. Bernstein! Sometimes Down, But Never Out” – a collection of articles and lectures that Jules Bernstein ’57 has published and delivered over a number of years, some of which are autobiographical and others that deal with labor, economic, political, historical, and law-related subjects.

Stay tuned for the next Bernstein essay on Brandeis and the history of ideas.

About the Author

Jules Bernstein has been practicing worker and union-side labor law from Washington, DC, since the early 1960s. In addition, he has participated in many labor-organizing and bargaining struggles throughout his career. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1935, and is a graduate of Brandeis University (BA 1957); the University of Chicago Law School (JD 1960); and the New York University Law School (LLM 1961). He served on the legal staff of two large unions for the first two decades of his career and has been in private law practice with his wife, Linda Lipsett, for the following 40 years, where they continue their law practice together.