Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

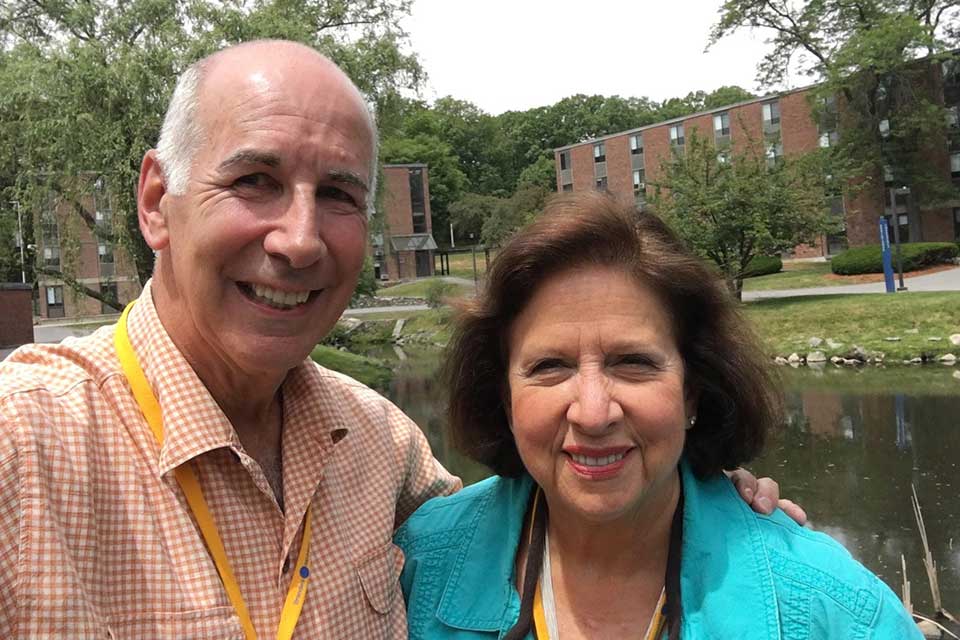

When Harry Met Brandeis

Michael Leiderman ’66 recalls Brandeis commencement ceremonies over the years, with one in particular ending in perfect harmony.

Photo Credit: Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University

Commencements are normally pretty staid affairs. Graduates sit through the speeches, get their degrees, maybe throw mortarboards in the air and move on. But Brandeis commencements, at least those I attended, were anything but routine.

Reflections of the Times

My own commencement, in 1966, nearly didn’t happen. Opposition to the Vietnam War had captured the nation’s consciousness and student protests were already common. When the University chose the Johnson Administration’s UN Ambassador, Arthur Goldberg, to give the commencement address, our class planned to stand in silent protest during his speech. We intended to show we opposed the war while respecting the ambassador by not disrupting the speech itself. Although the demonstration would be peaceful, Dr. Sachar was furious. The iconic Brandeis president refused to allow the protest and had Waltham police arrest several students who were passing out leaflets explaining our intentions. Eventually, our classmate Allen Zerkin negotiated a last-minute resolution that allowed the students to be released, the protest to take place and the ceremony to go on. We had a graduation after all.

Commencements were smaller and reunions fewer at Brandeis in those days, so the University held both events over the same weekend. Members of the reunion classes who had spent the previous two days celebrating their Brandeis experience would often take in the Sunday morning commencement exercises outside in the old Ullman Amphitheater, before heading home.

That was the plan when I returned to campus in 1971 for our fifth reunion. With Vietnam at its height, the draft building up and continued threats of anti-war disruptions, the University moved its undergraduate commencement out of the amphitheater to the open field by the Three Chapels. Caps and gowns were eschewed and, rather than marching in a procession, graduates seemed to drift into the ceremony at will, under the watchful eye of the local cops. All remained calm, though, and the event took on the feeling of a giant picnic, minus food, but with some distinct aromas wafting through the air.

Five years later, the mood was distinctly different. The war was over; Watergate had brought down Richard Nixon, the oil embargo created gasoline queues that ran for blocks, Gerald Ford was president and the nation seemed on auto-pilot, just trying to get by. Congresswoman and civil rights activist Barbara Jordan had a different vision when she addressed the 1976 Brandeis commencement audience. “Where are your voices?” she demanded. “Brandeis was always known for social action; for its progressive student body, for making noise to change the system. But now it seems you students have become a silent part of the establishment. You’re much too self-satisfied, much too quiet,” she told us. “We in government need to hear from you.” Her message jolted us to attention.

Seizing and Elevating the Moment

But it was our 25th reunion that made for my most memorable - and unexpected - commencement experience. That June morning, a fellow classmate and I found a spot on a small hill off to the right of the Ullman stage. We waited for the procession to file in from the assembly area at the Gryzmish Academic Center. Polite applause greeted the honorary degree recipients. There was plenty of star power - scholars, entrepreneurs, author Philip Roth - who, one by one, reached the top of the amphitheater and walked down the aisle to the stage.

Then Harry Belafonte appeared. He would receive a Doctor of Humane Letters.

The audience reaction was instantaneous. Everyone broke out into cheers, applause, shouts, whistles. The convocation was in an uproar.

“Go figure,” I said to my classmate. “You have all these geniuses getting honorary degrees and everyone’s cheering the singer?”

She just stared at me and shook her head.

“Don’t you realize Belafonte IS Brandeis? He’s a crusader, a fighter for social justice his whole career. He is everything Brandeis is supposed to represent.”

Suitably chastened, I watched the proceedings unfold. Students got their degrees; the keynote speaker said something like “wisdom is the tears of experience,” but this would be Belafonte’s day.

Harry was beaming as he crossed the stage to receive his honors. He looked frail, though, his gait a bit slow and stooped. There were rumors that his voice was no longer the rich instrument we had known. We heard that his throat hurt so much, he was unable to speak at the president’s dinner the night before.

Belafonte bowed graciously as the ceremonial robes were placed onto his shoulders and he was handed his honorary degree. But instead of returning to his seat, he turned and headed to the podium. The audience started to buzz.

“I know I’m not supposed to give a speech,” he said at the lectern. “But I must tell you: today I can’t help myself.”

“You have no idea how much this honor means to me,” he continued. “All these years, Brandeis and I have been on the same side, fought for the same ideals: civil rights; human rights; justice; freedom; an end to bigotry and racism. We have marched together. We have faced the worst, but survived and achieved. And there is so much more we have to do - together. Thank you, Brandeis!”

The throng exploded with more cheering and applause. But he was just getting started.

“I am so happy today,” he said. And when I am happy, I like to sing. Won’t you join me?”

And Belafonte began:

“Day-O! Day-Ay-Ay-O! Daylight come and me wan’ go home…”

“Day-O! Day-Ay-Ay-O! Daylight come and me wan’ go home…”

We looked at each other in amazement, then joined in as Harry Belafonte led the entire commencement singing his signature pop hit, “Day-O: The Banana Boat Song.”

“Come, mistah tally man; tally me banana! Daylight come and me wan’ go home…”

His lilting voice was the one we remembered from years past, full, strong and pure. Tears of joy ran down our faces as we all sang along. A moment no one expected had given the morning a significance I would never forget.

As Brandeis grew, the University moved commencement and reunions to separate weekends. I’ll miss those commencement Sundays, though. They were a bonus that always promised something different. I never knew whether I’d end up in a protest, a challenge, or even a sing-along. What I did know was, like Brandeis itself, the experience would be unforgettable – and one to treasure.

A Response from David Schindler ’98

I just read with joy Michael Leiderman's story about Harry Belafonte. I have a Harry Belafonte story of my own. My grandfather, Abraham Schindler, escaped death in the Holocaust by working in a factory as a trained electrician. He worked in a leather goods factory for most of the war, and because of that, he was protected, in a story similar to "Schindler's List." When the war ended, after living in a displaced persons camp with my grandmother and my father he was sponsored and emigrated to America. In the US, he faced a new racism: Jews were not allowed in the electrician's union, and if you weren't in the union, you could not work. So my grandfather did odd jobs for years order to feed his family in New York City. And who hired him? Harry Belafonte heard about his plight, a Jew who survived the Holocaust, only to come to the US and be forbidden from working because of the powerful anti-semitic electrician's union. Harry Belafonte hired my grandfather to work in his studio, to do odd jobs, and that helped feed my family. I have Mr. Belafonte to thank for all I have been given.