Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

An Overdue Apology to Fred P. Pomerantz

“You must read ‘Button Man,’” my dinner companion told me. “It’s a novel about Jewish mobsters in the 1930s and how they took over the garment unions.” The subject sounded intriguing and when two other friends also suggested that I read it, I figured I’d give it a try. Little did I know that it would take me back to a chance meeting during my Brandeis days that left a lasting impression.

Listen to Mike Leiderman ’66 recount his story of a chance, but meaningful, encounter during his Brandeis days.

“Button Man,” a recent work of historical fiction by author Andrew Gross, grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. I finished it in two days and marveled at the protagonist — Morris Raab — son of Jewish immigrants who rises from the tenements of Manhattan’s Lower East Side to build a multimillion-dollar garment manufacturing empire. Not only does he prevail over poverty, but he fights against mobsters like Louis Lepke and Jacob Gurrah who destroy his first factory and nearly kill him when he continues to resist their muscling into the industry.

Lepke and Gurrah control the garment unions. They force manufacturers to enroll their employees, promising them higher wages and added benefits. Once the businesses sign up, employees see their supposed pay increases going into the pockets of corrupt union heads and mobsters. The mob also forces factory owners to buy substandard goods at inflated prices from union-approved suppliers. Manufacturers, in turn, raise their own prices. Buyers find other outlets, leaving the workers jobless and the factories broke. By then, the union has pocketed hundreds of thousands of dollars and moves on to new companies to pillage.

Success Despite the Odds

The Morris Raab character is different. He quits school at age 11 to work in a garment factory to help support his family. By 15, he is running the factory and owns his own business before he is 21. While he has little formal education, Morris has a genius for the industry and a toughness even the gangsters grow to respect.

His road is perilous. He sees other garment businesses ravaged by mob greed, firms forced into bankruptcy and workers and their families left destitute amid the Great Depression. Only the mobsters profit, taking in millions with their rake offs.

Those who resist fare even worse. Factories are ransacked and torched, inventories destroyed, shop owners and honest union representatives assaulted, maimed or murdered. The police are of little help; too many are in the pockets of the mob. A corrupt police investigator tells Morris his report would say Raab’s factory wasn’t destroyed by arson, but by a boiler explosion, so there will be no further investigation.

Raab’s determination to build his business and fight the mob makes a compelling novel. But I found there was even more to the story, and here’s where Brandeis comes in.

An Unexpected Connection

I don’t often read the chapter of acknowledgements at the end of a book, but something made me do it this time. There, I discovered the character of Morris was based on Gross’s grandfather, who similarly rose from Lower East Side tenement life to become a successful manufacturer of iconic brands of women’s clothing. As he prospered, Gross’s grandfather also became a noted philanthropist. He dedicated a building to New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology and funded others that bear his name on college campuses across the country. The grandfather’s name: Fred P. Pomerantz, the real Morris Raab of “Button Man.”

That’s when I remembered: As a Brandeis sophomore more than 50 years ago, I lived in Gerta and Fred P. Pomerantz House.

My friends and I called our dorm simply, “East Quad.” Who cared about the name? There were so many of them on every Brandeis building: Goldfarb, Rose, Kutz, Shapiro, Olin-Sang, Renfield, Lemberg, DeRoy, Swig, Hassenfeld, Mailman, Slosberg, Spingold, Gryzmish. But, yes, Pomerantz was our official home

A Visit from the Namesake

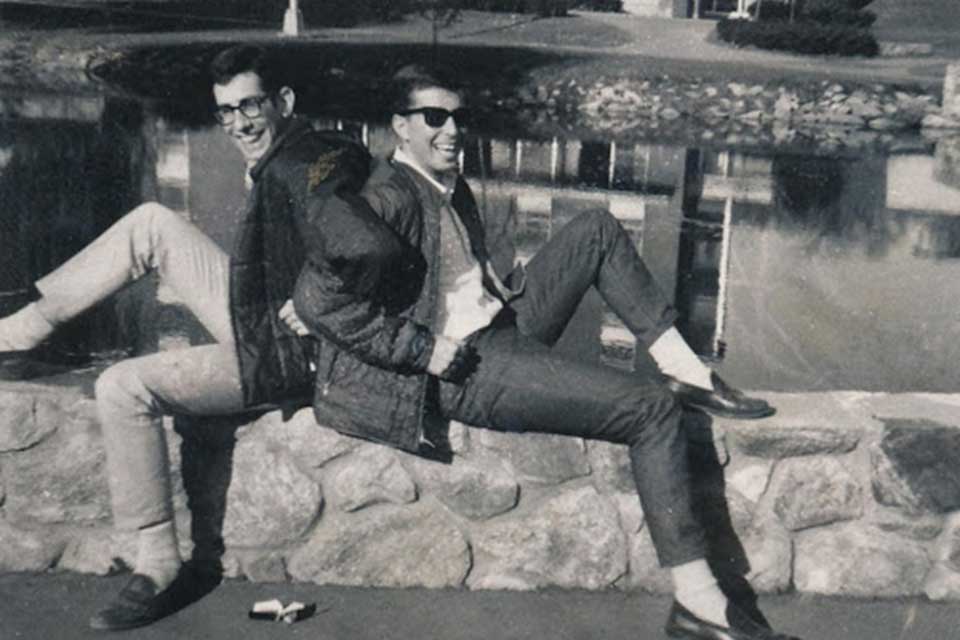

The new East Quadrangle opened in the fall of 1963. For some reason, none of the upperclassmen wanted to live there, so we sophomores were assigned to the dorm and our wing was named in honor of Fred P. Pomerantz and his wife, Gerta. The 10-man suite (women were housed in the other end of East Quad) featured two single rooms, four doubles and a central lounge where we’d gather to shoot the breeze, watch TV and stock or raid the fridge. Those in the lounge would hear their suitemates calling out from their rooms: “Hey, shut up! Some guys are trying to study.”

Several of us were in the lounge one afternoon when a well-dressed Brandeis administrator strode into the suite and announced: “Would you all rise and meet Mr. Fred P. Pomerantz!” The tone of her voice indicated this was an order, not a request, while the look in her eyes seemed to say: “Please, show some respect.”

Our group was caught off guard. “What?” “Rise and meet?” This was our space and the only person we’d probably get up for — including Abe Sachar — was the sandwich man or the delivery guy from Gordon’s Liquors.

After a few awkward seconds, we managed to get to our feet when the man walked in. He was barely five-feet tall, with a build like a fire hydrant, a face like a clenched fist and a no-nonsense expression.

And so we met Fred P. Pomerantz. He looked around, said nothing, grunted and walked out. As the pair left, one of us called out, in a voice dripping with sarcasm: “Thank you for our school.” We all laughed. Thankfully, Mr. Pomerantz and the Brandeis rep were out of earshot.

Reliving that scene today, I think: what an opportunity missed. We were 18- and 19-year-olds, full of naïveté and privilege. The arrival of Mr. Pomerantz was an interruption; no, an annoyance. We resented the fact that every structure at Brandeis seemed to have a name on it — never mind why — and bristled at the thought of paying homage to some old benefactor who couldn’t score 1300 on his SATs.

And yet, somehow, that moment has stuck with me for decades. I talked to a couple of my suitemates recently and they, too, remember it vividly. But it was only after reading “Button Man” that I finally understood its significance.

Gratitude and a Few Regrets

Fred P. Pomerantz was a legend. Despite his sixth-grade education, he had more smarts than anyone in that dorm room of ours. He rose from the streets to be a captain of industry, deserving the utmost respect. He fought the gangsters and nearly paid with his life — Gross said he would proudly show off his scars from stab wounds inflicted by Jake Gurrah. He built a billion-dollar empire with honesty and determination. And he shared his wealth to ensure others received the formal education he never had.

Wouldn’t it have been fascinating to talk with him then — to learn from him, hear his stories and philosophies? That would have been as valuable as any course we’d ever take.

Perhaps he wouldn’t have wanted to chat. Gross said his grandfather, embarrassed about his lack of proper grammar and diction, felt uncomfortable around strangers who were better educated.

Yet his grandson also said Fred P. Pomerantz loved to tell his stories. Chances are he would have been more than willing to spend time with us.

So, Mr. Pomerantz, nearly 60 years later, please accept my apology. My older self would have been honored to “rise and meet” you and learn from you back then. And yes — thank you. Thank you very much for our school.

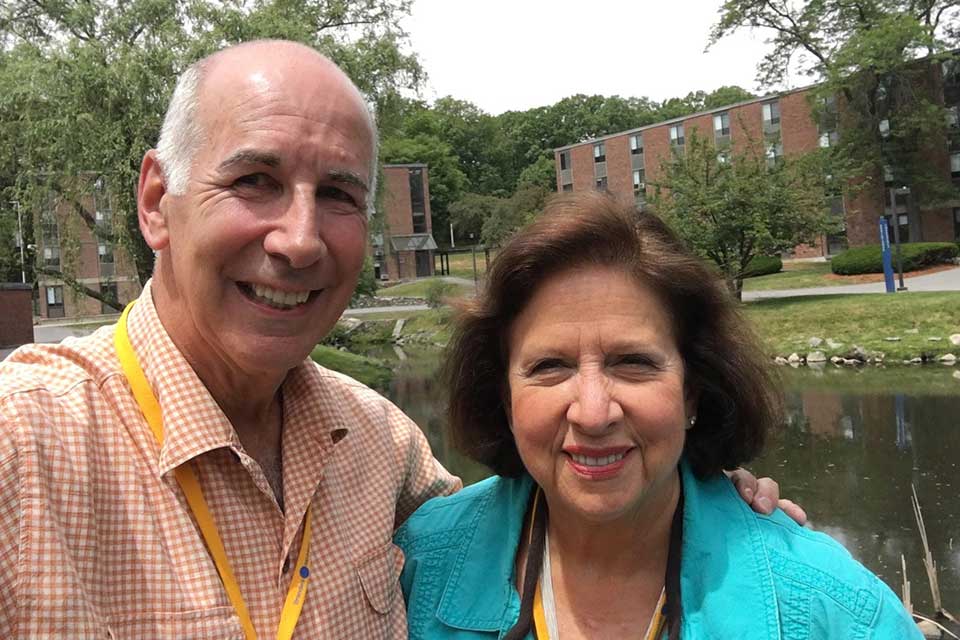

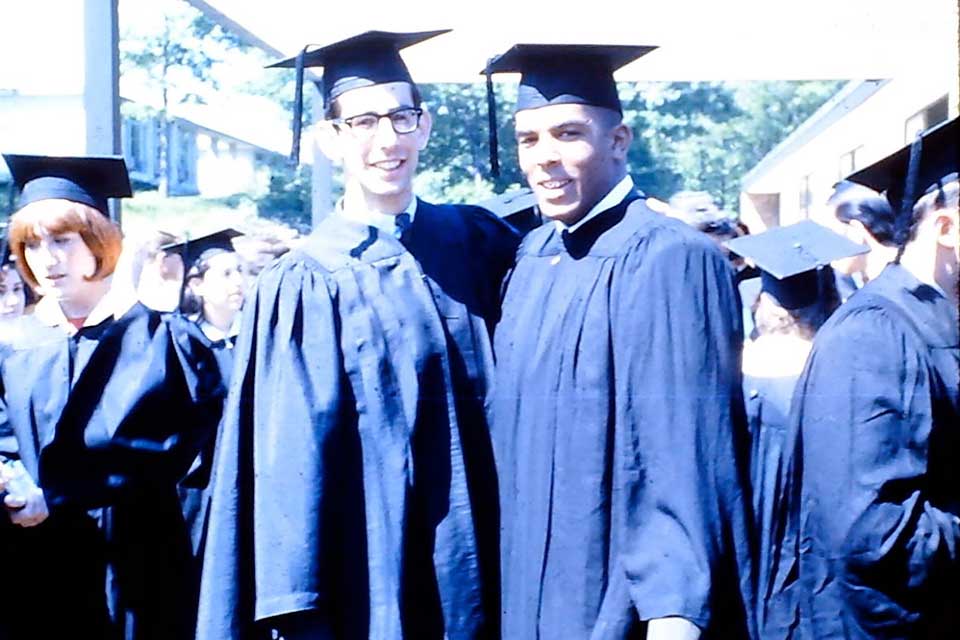

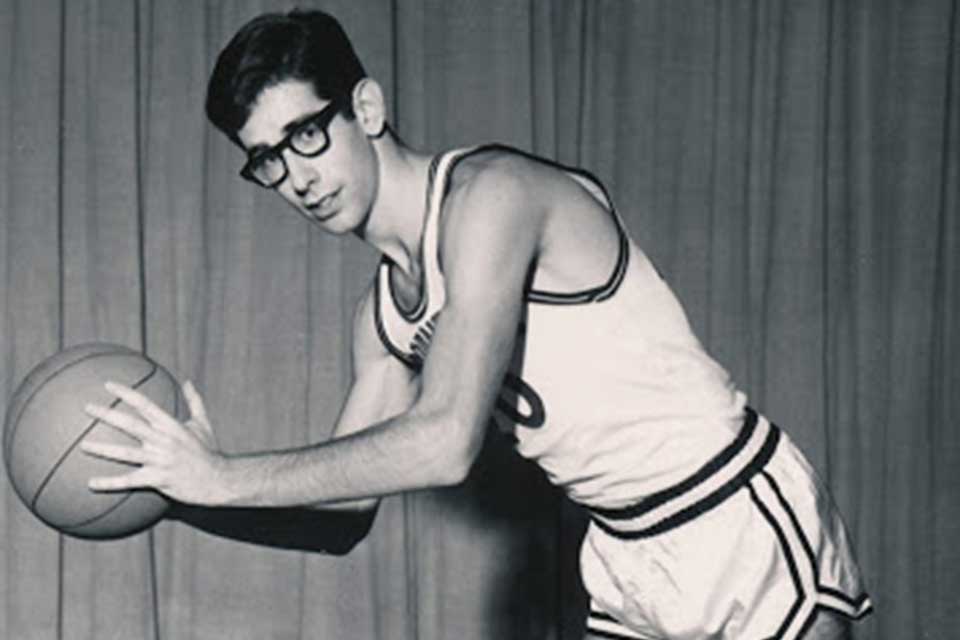

Mike Leiderman ’66 is a retired broadcaster, sportscaster and producer. He graduated from Brandeis cum diploma. He is serving on the Class of 1966’s 55th Reunion committee.