Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Finding Comfort and Community Amidst a 1970s Lettuce Boycott

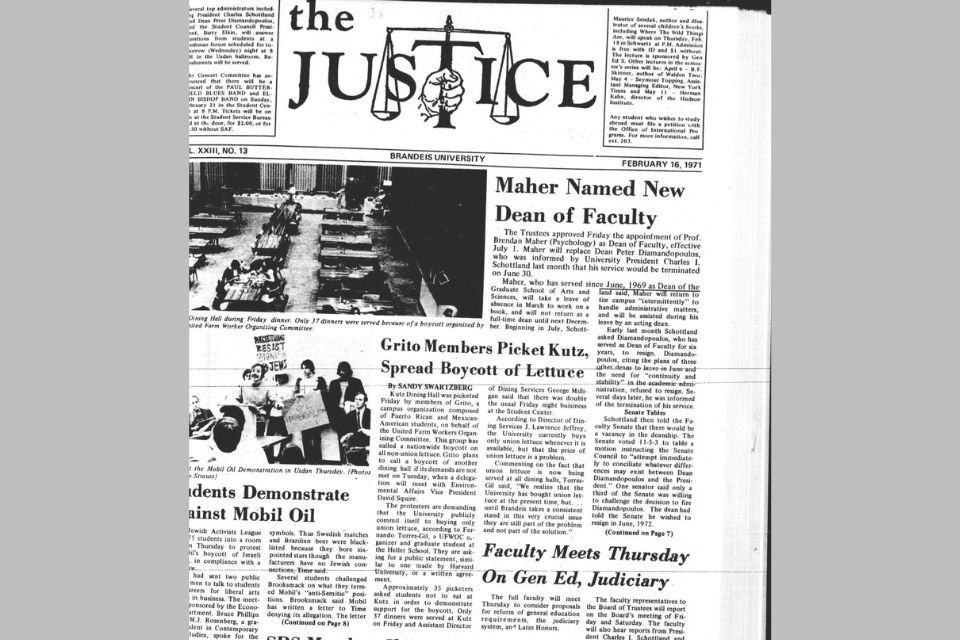

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month – the period from September 15 to October 15 that recognizes the contributions and influence of Hispanic Americans to the history, culture, and achievements of the United States – the Brandeis Alumni Association spoke with Elvira Castillo, a Mexican American/Chicana who attended Brandeis as a student in the early 1970s. She’s pictured in a 1972 photo, holding a sign that reads: “Don’t Shop AP. Boycott Lettuce.” Fifty years later, here is the story behind the photo.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Elvira Castillo

Activism in action

When winter came to Waltham in 1972, Elvira Castillo was still getting acclimated to the cold. She had grown up in Gilroy, California, a small farming town 80 miles south of San Francisco and 30 miles north of the Salinas Valley, known as the “salad bowl of the world” for its vibrant agricultural industry.

Growing up, Elvira attended a small, rural public school whose student body consisted of Mexican, Filipino, and Japanese kids whose parents worked the farmland. In the summer, some of her classmates worked alongside their parents in the fields and packing houses. “I learned how to drive a tractor before I learned how to drive a car,” she says with a smile during a recent Zoom conversation.

Originally from Mexico, her father came to the United States as part of the Bracero Program, a government-sponsored initiative that brought in Mexican laborers to aid the American agricultural economy following labor shortages stemming from World War II. But it wasn’t just her father who worked the land. As the oldest of eight children, Elvira recalls changing out of her school clothes to help her parents in the vegetable packing houses and in the field, harvesting crops like garlic, cucumbers, bell peppers, and tomatoes.

While her father never talked about the low wages, poor working conditions, or lack of recognition for helping to produce food for the nation, she experienced it firsthand. She recalls walking out to the irrigation ditches to go to the bathroom because they didn’t have access to porta potties. They lacked access to clean drinking water, too. Her skin reveals the effects of a childhood spent in the fields: “Now that I’m 70, I look at my arms and see age spots from the sun. That was before sunscreen,” she says. “People would say, ‘No, you’re brown, you’re not going to get cancer,’” she laughs wryly.

That Elvira had even heard of Brandeis was due to efforts by the United Mexican American Students, a group founded by students from the Boston area colleges and universities. UMAS challenged colleges to expand recruitment of Latino students living in the southwestern part of the country.

When she got to Brandeis, Elvira recalls there were about two dozen Latino students in her first-year class, hailing from Texas, New Mexico, California, and New York. A small group of Latino students who were on campus before Elvira got there had founded a student group, Grito. Grito hosted parties, campus speakers, study groups, and protests.

The word grito means “shout” or “cry” in Spanish, and also has references to a “cry of independence” in Mexico (El Grito de Dolores) in 1810 and the Puerto Rican pro-independence movement of 1868 (El Grito de Lares).

One such protest was a lettuce boycott at the local A&P in Waltham. Elvira decided to participate for a number of reasons.

“It was a way to meet different people,” she says, “to find out news about what was going on in California, to take away my homesickness for a while, and to connect me to my pre-Brandeis life. It was a pressure release from being a student so far away from home in a totally different environment.”

While she was familiar with the experiences of farmworkers in California, having lived with them, and aware of the extreme exploitation they faced, she never really connected the broader impact of the farmworkers’ rights movement, led by Cesar Chávez and the United Farm Workers to the Brandeis campus, until one day in the cafeteria.

“I saw some students go to the salad bar and empty out the lettuce on the ground. I wasn’t that brave – I didn’t want to jeopardize my scholarship – but I learned that the boycott was so much bigger than the A&P.”

The campus lettuce boycott, led by Grito, made the front page of The Justice on February 16, 1971, quoting Fernando Torres-Gil, MSW’72, PhD’76.

Enduring connections and pride

While Elvira ended up transferring to Pomona College after her sophomore year, to be closer to home, she has remained close to her Brandeis friends, recently taking a road trip from San Antonio to Albuquerque and visiting Brandeisians along the way – “the people who added to my life 50 years ago.”

In 1987, Elvira was working in Washington, DC, with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, when then-Congressman Esteban Torres (D-CA) introduced legislation extending Hispanic Heritage Week into a month. “I was part of that effort,” she says proudly.

To her, Hispanic Heritage Month is about “the recognition of Latinos’ contributions to making this country what it is, from railroads to mining to the arts and literature, leaders in the world of politics” to farmworkers, like her parents.

Elvira is also mindful of the hard work and sacrifices of present-day frontline wageworkers, many of whom could not work from home during the pandemic.

“Who was delivering my Instacart groceries?” she asks. “How can we recognize their contributions to the economy and grant them equity in this country?”

From the lettuce boycotts of the 1970s to the hardships that members of the Hispanic and Latino community face today, Elvira’s depth of compassion and courage in telling these stories is part of why Brandeis is so fortunate for her friendship and strong connection to campus. She still speaks enthusiastically about the “world” that Brandeis opened for her and continues to encourage young people to seek their education away from their comfort zones.

Do you have a photo or memory from your time on campus that relates to Hispanic Heritage Month? Let us know and we may share it on our social media channels.

About the Author

Alexandra Stephens is the assistant vice president of advancement communications at Brandeis University. Since joining the Brandeis community in 2010, she has held numerous roles across student affairs, alumni engagement and communications, and has connected with hundreds of alumni and friends to help share their inspiring stories. Outside of work, she is a LinkedIn coach, yogi, home chef and mom of two.