Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

‘Walking History’: Pauli Murray's Legacy at Brandeis

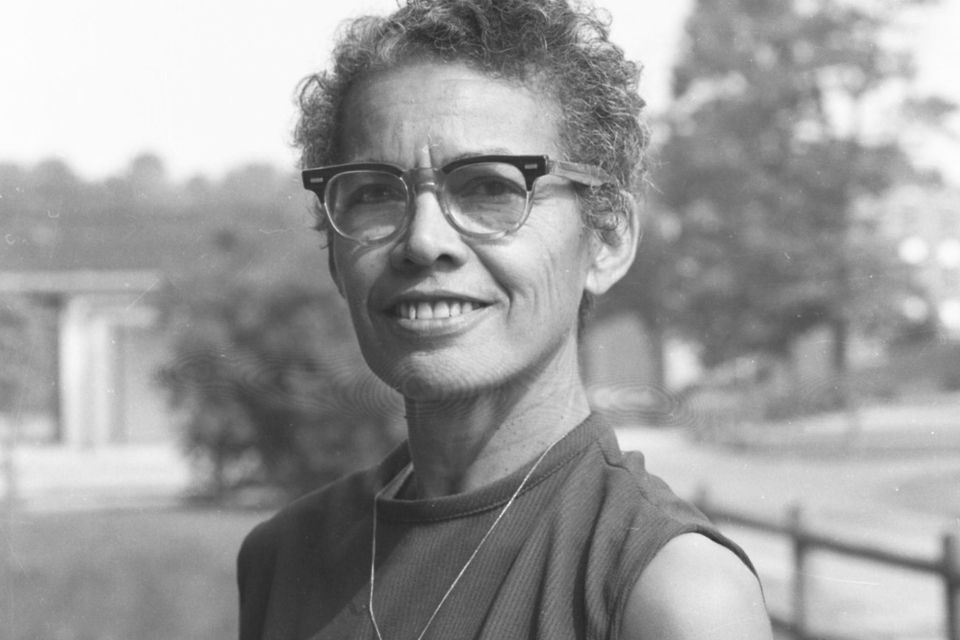

A new documentary looks at the extraordinary life and hidden contributions of former Brandeis faculty member Pauli Murray.

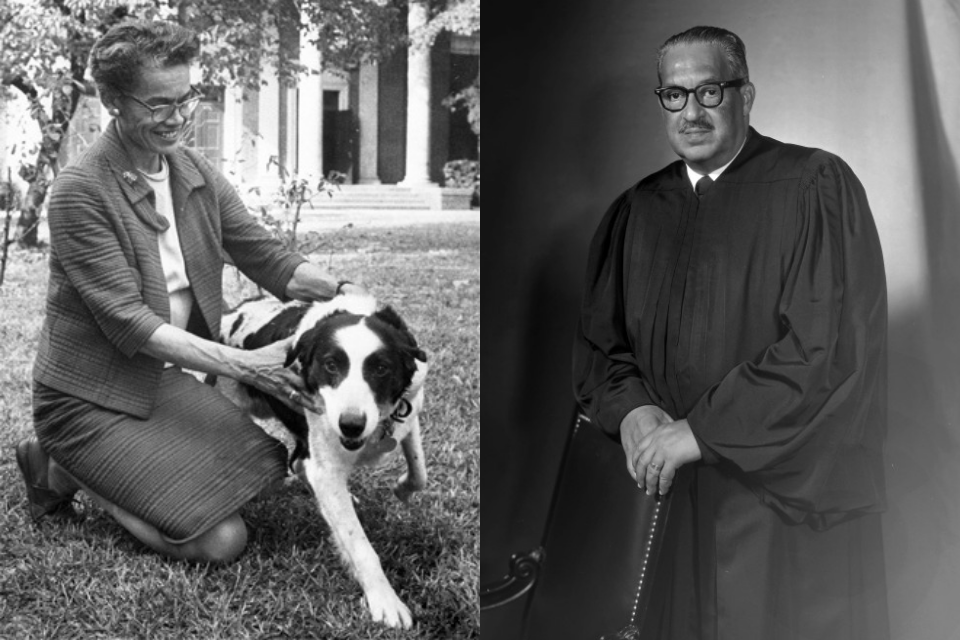

Photo Credit: Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections

Seventeen years before the Woolworth lunch counter sit-ins, Pauli Murray helped organize a sit-in that desegregated a restaurant in Washington, DC.

Fifteen years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat, Pauli Murray was arrested when she wouldn’t move to the back of a Durham, North Carolina, bus.

Ten years before Brown vs. the Board of Education, Pauli Murray advocated a legal argument that “separate but equal” is unconstitutional.

And decades before the term “intersectionality” was coined, Pauli Murray was grappling with gender identity, sexuality and race.

A new documentary streaming on Amazon Prime opines that you can’t teach American history without teaching about Pauli Murray — the Black feminist professor who taught at Brandeis for five years, nonbinary poet, civil rights activist and lawyer-turned-Episcopal priest, whose once-radical ideas provided the foundation for landmark civil rights legislation. Still, her name is relatively unknown. “My Name Is Pauli Murray” is trying to change that.

Complex ideas amidst complex times

“Over half a century ago, Pauli Murray created the groundbreaking legal strategy of some of the most important victories of our time,” says Julián Cancino, director of the Gender and Sexuality Center at Brandeis. The film outlines Murray’s role as a legal trailblazer whose ideas influenced Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s fight for gender equality and Thurgood Marshall’s civil rights arguments. “As an advocate for the inclusion of ‘sex’ in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Murray set the intellectual foundation for ‘on the basis of sex’ arguments. These arguments ultimately secured equal protections for women in the 1970s and, in a landmark Supreme Court ruling in 2020, ensured that LGBTQ+ people can get a job and work free from discrimination and harassment.” Ginsburg was quoted as saying, “Pauli was saying things far earlier than people were ready to accept.”

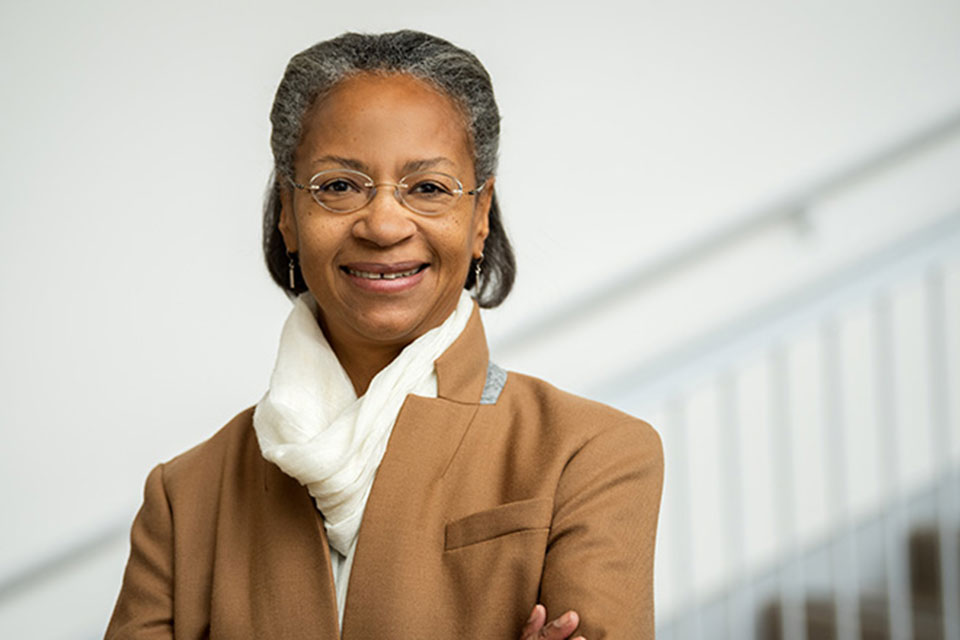

But Murray found acceptance at Brandeis. At a time when college students across the country were demanding the creation of Black studies programs, Brandeis hired Murray as a professor, where she taught from 1968 to 1973 and was appointed the Louis Stulberg Professor of Law and Politics. “Passing Pauli Murray’s photograph in one of our campus buildings since I began teaching at Brandeis in the mid-1990s reminds me that I mark time in this institution in the wake of the time served by African American faculty such as Murray,” says Faith Smith, chair of the Department of African and African American Studies at Brandeis.

The film references the undergraduate legal studies coursework Murray developed at Brandeis, but she also created the first courses in African American studies and women’s studies at the university and helped transition the American Civilization program into the American Studies program that exists today.

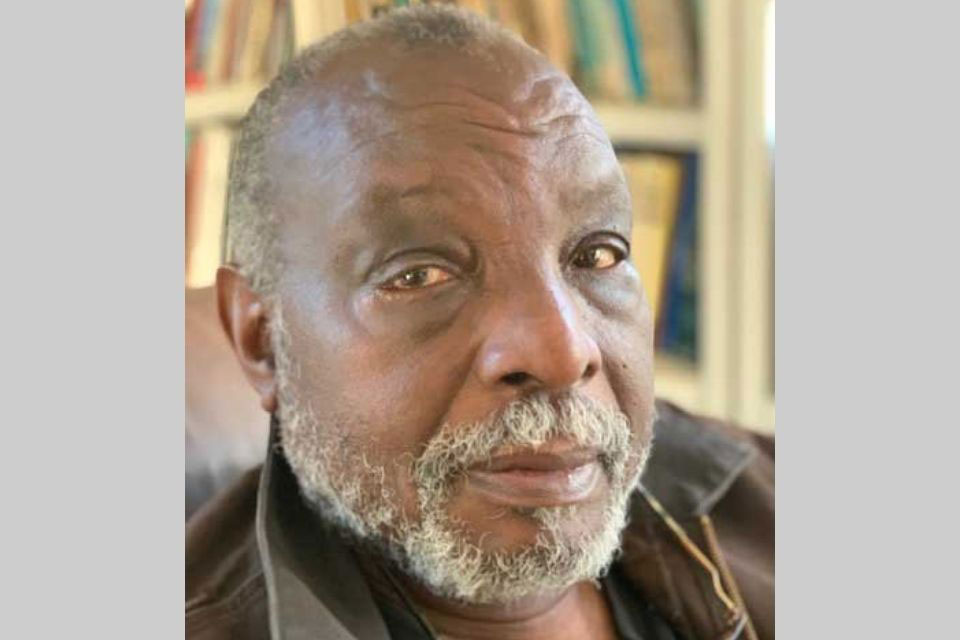

Two alumni from the first cohort of Transitional Year Program scholars at Brandeis, now known as MKTYP, appeared in the documentary to share recollections of their former professor and their days on campus, including as student-activists in the Ford Hall takeover in 1969. Reggie Sapp ’73, MA’05, G’13, and Ernest Myers, TYP’69, P’06, spoke about their first encounter with Murray, their discomfort with their professor’s preference to use the term “Negro” to describe Black people, and her trouble understanding the Ford Hall sit-in. Though she disagreed with their approach — occupying the building which housed Murray’s office — their goals were the same: to demand a more inclusive and equitable experience for Black people.

The former students added that Murray opened her home to them and, despite her brilliance, they never felt inferior in her presence. She just showed them how much more there was to learn.

“The Black students, who wanted to be like Black Panthers, thought she was a Tom, just by the way that … she didn’t like the takeover, she didn’t like the word ‘Black.’ But if that’s all they knew, they were missing the point. For any Black kid on that campus and any woman on that campus, she was walking history,” Myers said in the documentary. Both Sapp and Myers died in 2021, shortly after the film’s release.

“Murray’s life and work anticipate some of the questions that perplex us today,” adds Smith. "First, Black people's negotiation of normative racial and gendered identities invites a continuous reckoning with all expressions of identity. Secondly, a profound generational chasm separated Murray from the Black students whose call for a separate department, among other demands, led to the takeover of Ford Hall in 1969… For me, this unease with the institutionalization of Black studies anticipates our current moment of reckoning with an academic life in which Blackness remains both hypervisible and invisible, and Black studies both better and under-resourced.”

‘Way ahead of the curve’

Nina Koocher ’71, P’13, recalls a formative experience with Pauli Murray, her former professor.

“As a junior at Brandeis I took a seminar with Pauli Murray. I still remember the light coming in through the west facing windows of the Rabb Graduate Center illuminating Dr. Murray’s face as she sat at the head of our seminar table. Dr. Murray was always dressed in a suit and frequently smoked a cigarette. She had a strong presence and a wide smile. Dr. Murray treated her students as intellectual equals and gave each of us an opportunity to explore with her issues of gender and equality in today’s society.

“As part of the seminar I did a paper on gender differences. I researched the phenomena of hermaphroditism, the presence of both testicular and ovarian tissue in the same individual. I read about infants whose gender was chosen for them by the attending physician and the difficulties this created as these children grew. At a time when these issues were not being discussed, we were exploring gender and transgender, Nature vs. Nurture and how these phenomena influence identity. Needless to say, we were way ahead of the curve.

“Of all the classes I took at Brandeis this was one of the most memorable. I knew that Dr. Murray had been a protégé of Eleanor Roosevelt but it is only now in retrospect that I understand the enormity of the intellect and the breadth of experience, personal as well as professional, that Dr. Murray brought to the table. Her willingness to share so much of herself encouraged all of us to be independent thinkers. She gave each of us the unspoken permission we needed to think for ourselves and to pursue our individual destinies.”

A singular mind

Murray was attracted to Brandeis because of its social justice roots and her deep friendship with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, H’54, a Brandeis trustee and visiting lecturer, who delivered the first Commencement address to the pioneering Class of 1952. “One of my finest young friends is a charming woman lawyer, Pauli Murray, who has been quite a firebrand at times but of whom I am very fond,” Roosevelt said of Murray in a 1953 feature for Ebony Magazine.

“She was definitely ahead of her time,” says Joyce Antler ’63, the Samuel J. Lane Professor Emerita of American Jewish History and Culture and Professor Emerita of Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies, “a pioneer in an amazing number of fields. But coming from real-world politics and legal scholarship, she had never taught in a liberal arts institution like Brandeis. She saw it as her ‘big chance.’”

For Brandeis’ part, the film notes that Murray was initially denied tenure, on the grounds that her published writing was not up to standard, but she appealed and ultimately won tenure with support from her mentor Lawrence Fuchs, who co-founded Brandeis’ American Studies department. “I think Larry Fuchs understood that her real-world activism and her role in the civil rights movement and feminism would be instructive for students. When she came, she was encouraged to innovate,” adds Antler.

That said, Antler and Smith, like many other historians, are disappointed that Murray’s life and legacy remain relatively unknown.

“It’s disheartening,” says Antler. “She bridged so many movements and periods and was an activist and leader in so many areas — the legal world, feminism, civil rights. Perhaps her versatility and deep involvement in many things make the breadth of her contributions difficult to acknowledge.”

“This new film demonstrates that we are always trying to catch up to Murray,” adds Smith.

Make a gift in honor of Murray to a Brandeis fund related to the causes she championed.

Additional Reading

“Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest, and Poet” by Pauli Murray

“Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage” by Pauli Murray

Pauli Murray’s poetry (Listen to Pauli Murray read “Dark Testament”)

"Pauli Murray: The Brandeis Years" by Joyce Antler (Journal of Women’s History, 2002)

“The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship” by Patricia Bell-Scott (Penguin RandomHouse, 2017)

“Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray” by Rosalind Rosenberg (Oxford University Press, 2017)

About the Authors

Alexandra Stephens is the assistant vice president of advancement communications at Brandeis University. Since joining the Brandeis community in 2010, she has held numerous roles across student affairs, alumni engagement and communications, and has connected with hundreds of alumni and friends to help share their inspiring stories. Outside of work, she is a LinkedIn coach, yogi, home chef and mom of two.

Since leaving the daily newspaper world, Abby Klingbeil has been helping organizations tell their stories in a way that inspires action. After nearly a decade at the University of Washington in Seattle, she returned to the East Coast and has worked with Tufts University, MIT and now Brandeis. She has won numerous awards for her writing and communication projects.