Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

A Kinder, Gentler Web

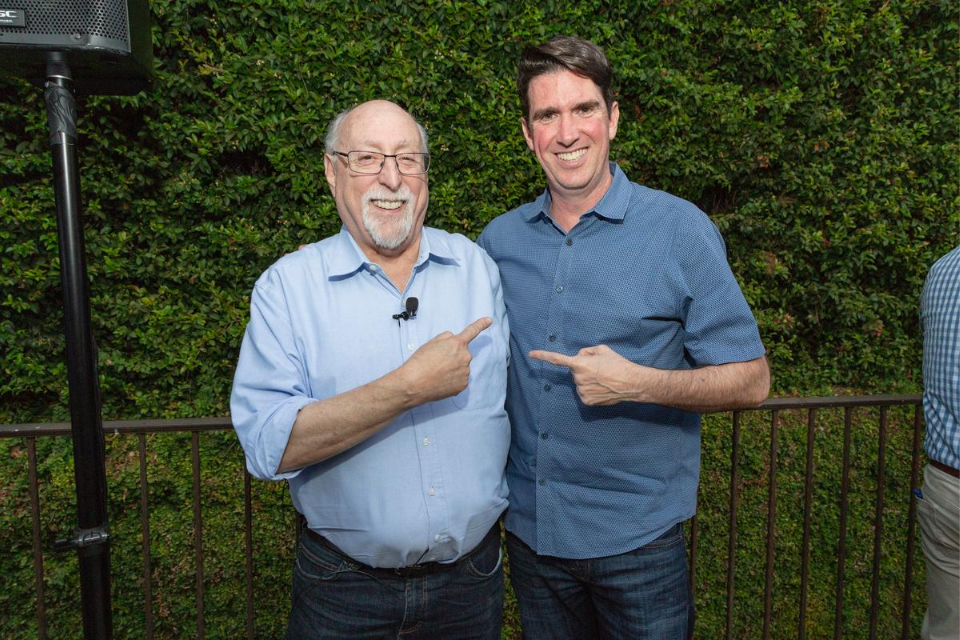

Former Facebooker Sahar Massachi ’11, GSAS MA’12, is leading a group of tech visionaries who want to rid the internet of spam, scams and vitriol.

Photo Credit: Mike Lovett

In the decade since Sahar Massachi ’11, GSAS MA’12, earned a bachelor’s and a master’s in computer science at Brandeis, he has co-founded two failed startups, helped Wikimedia fine-tune its fundraising, tested the efficacy of soft-money ads for presidential candidate Joe Biden, and won fellowships that nurtured his leadership skills and gave him time to think deeply about tech and society.

He also serves on the advisory committee of the university’s Louis D. Brandeis Legacy Fund for Social Justice and runs Yenta, a sideline project that helps subscribers find housing, work or romance.

But nothing influenced his current job — as co-founder and executive director of the Integrity Institute, a new heal-the-internet venture that has already been the subject of stories in Wired, Protocol and The Wall Street Journal — more than the nearly four years he worked at Facebook. “It really shaped who I am today,” he says.

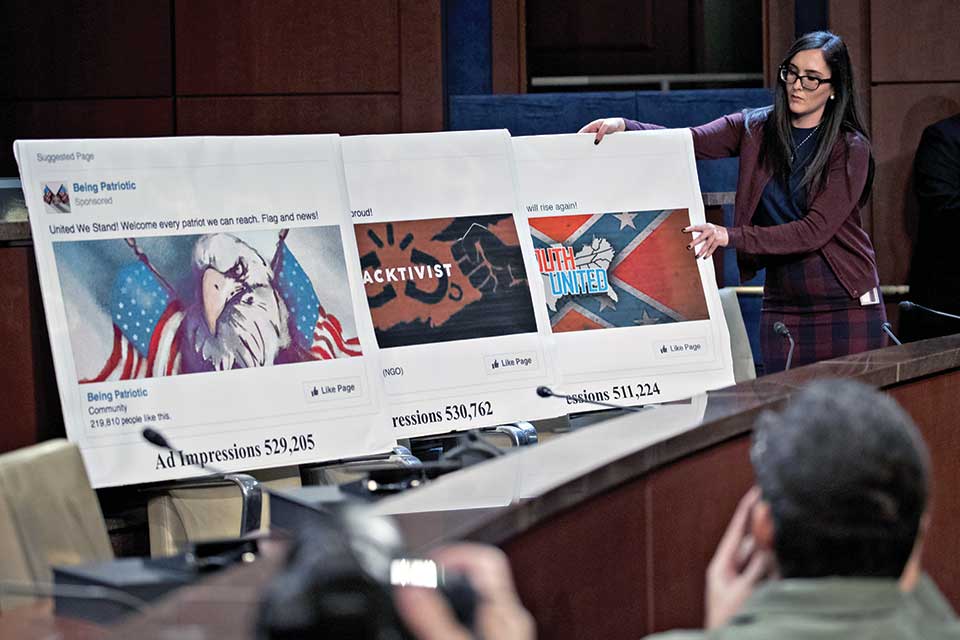

As a software and data engineer on Facebook’s Civic Engagement and Civic Integrity teams from 2016-19, Massachi developed tools to foster political involvement, and rein in malicious efforts to skew public opinion and undermine democratic elections around the world.

Some of the tech he created has been discussed by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Some remains secret. Internal documents shared by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen in 2021 highlighted the work of the Civic Integrity team — and showed how often its recommendations were disregarded by higher-ups more intent on maximizing profits.

In January 2021, Massachi and Jeff Allen, a fellow Facebook alum, began talking about starting an independent organization that would encourage greater adherence to integrity principles across the internet. They recruited potential members and invited them to a July retreat to develop the institute’s mission, including the problems it would address and the fixes it would propose. The nonprofit was incorporated in September.

Broadly speaking, the Integrity Institute brings people together to brainstorm, research and share best practices for creating a kinder, gentler internet, a place less riddled with spam, scams and vitriol. Institute members — all of whom work on a volunteer basis, for now — include several Facebook alums, as well as current employees of Twitter, Clubhouse and other major Silicon Valley companies.

In a Founders’ Letter published on the institute’s website, Massachi and Allen issue a call to action that evokes the idealism of Silicon Valley’s early days: “We’ve seen poisonous information ecosystems. We’ve seen some of the worst hate speech, bullying, hoaxes and bad faith you can imagine. And yet still, we believe. It is possible for the social internet to help us thrive: as individuals, as societies and as democracies. […] There is a path forward.”

This path isn’t yet entirely clear. Massachi demurs when asked whether the U.S. government needs to strengthen its regulation of social media companies, though he doesn’t rule that out. For now, he suggests, the institute is more intent on sharing information than on lobbying government officials.

The goal is to offer “people who are busy bailing out the boat a place to think about the theory of what they’re up to,” says Massachi. “We’re going to try educating journalists; educating policymakers; talking to academics; talking to big companies, small companies — whatever our members want to do, really. We’ll see what works.”

Photo Credit: Andrew Harrer / Bloomberg via Getty Images

A leader’s leader

Massachi’s life has been defined by his passions: for social justice, technology and community.

“He’s a leader’s leader,” says Jamele Adams, former dean of students at Brandeis, now director of diversity, equity and inclusion for the Scituate, Massachusetts, public schools. At Brandeis, “Sahar had this incredible energy as a champion of social justice. He led with his heart. He was fearless in his advocacy. If something was wrong, he absolutely would stand against it.”

Massachi’s parents are Iranian Jewish immigrants who came to the United States by way of Israel. His father’s family left Iran for Israel in 1963. His mother’s family fled Iran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which deposed the shah and installed a theocratic regime. “As far as I know, they left on the last-ever commercial flight from Tehran to Tel Aviv,” Massachi says. “And my mother’s father had to bribe their way on.”

How his parents met is “such a good story,” says Massachi. In Israel, his father failed English his sophomore year of high school and decided, in lieu of summer school, to move to Rochester, New York, where two of his older brothers had settled. He earned a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Buffalo and worked briefly at the Eastman Kodak Co. before deciding he wanted “to marry a nice Jewish girl.”

What better place to find one than Israel? Massachi’s father enlisted in the Israeli Air Force, where a fellow officer introduced him to his sister. After a bad first date, the two clicked and were married seven months later. During the 1990-91 Gulf War, the U.S.-led response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, “every family in Israel was given this airtight tent to be in during air raids,” Massachi says. “My mother was wearing a gas mask. I was 2 years old and bawling. She looked at my dad and said, ‘This is no place to raise a child.’”

So the family moved to Rochester, where his mother now teaches psychology at Monroe Community College and his father is a landlord. Massachi, who has two younger sisters, Shelly and Talie ’18, attended top suburban public schools, took accelerated math classes and read feminist fantasy fiction. He was reared to believe, he says, “that a police state was really bad, and that surveillance and censorship were the hallmarks of incipient fascism.”

When it was time to look at colleges, one of Massachi’s cousins, a Brandeis alum, urged him to check out his alma mater. Timothy J. Hickey ’77, professor of computer science, met with Massachi during his campus visit. “He was very engaged in social issues even at that point,” Hickey remembers, “and really interested in making change in the world.”

A Brandeis alumna who interviewed Massachi was the mother of a girl he’d had a crush on since the third grade. “If you go to Brandeis,” he recalls her advising him, “you will be a big fish in a small pond. You’ll have the time of your life. Girls will want to date you, and you’ll be very happy.”

Persuasive and, as Massachi discovered after he enrolled, all true. But, amazingly, it was that third-grade crush who ultimately became his romantic partner. Massachi reconnected with Sarah Winsberg, a Climenko Fellow and Harvard Law School lecturer, at a 2017 Hanukkah party. They now share an apartment in Somerville, Massachusetts, and are moving to Brooklyn this summer for Winsberg’s new job, as an assistant professor at Brooklyn Law School.

At Brandeis, Massachi started a social justice blog, innermostparts.org, which made him something of a campus celebrity. But his “foundational moment,” he says, came during the university’s 2009 financial crisis, when he organized student protests against officials’ plans to shutter the Rose Art Museum and shrink academic offerings. The administration eventually agreed to add students to committees discussing the university’s response to its financial difficulties. The Rose, which survived, is now marking its 60th anniversary.

In 2010, to counter antisemitic and homophobic protests by the Westboro Baptist Church, Massachi helped organize a Celebrate Brandeis day and raise funds for Keshet, a Boston-based Jewish LGBTQ group.

Massachi has more-carefree Brandeis memories, too: Climbing campus rooftops. Mapping the tunnels beneath the Castle. Helping to bake 31.4 pies for Pi Day. Setting off random alarms to circumvent the potential arrest of weed-smoking friends.

His Brandeis education, he says, included “learning when to break the rules, to do things that were objectively maybe a little perilous.”

‘A big, messy place’

Though he majored in computer science, Massachi didn’t expect to pursue a tech career. “I thought the coolest job in the world was working for [the progressive organization] MoveOn,” he says. “Then I got my master’s in computer science at Brandeis on a whim, and I accidentally founded a startup.”

Seeded by Brandeis with a $7,500 grant, the startup, Innermost Labs, made apps for conferences. Though it ultimately failed, Massachi says the whole experience “was really fun, and I learned a lot.”

The 2013 suicide of 26-year-old tech pioneer Aaron Swartz devastated Massachi. An advocate of open access to knowledge, Swartz was battling wire-fraud, computer-fraud and other federal charges for downloading academic-journal articles through MIT’s computer network. After refusing a plea deal, he took his own life.

Massachi regarded Swartz as “a deep and penetrating thinker” with great tech skills, someone “in conversation with the dominant progressivism of the day but also not captured by it.” His death, Massachi says, left him “despondent” and “full of rage.” One lesson he drew from Swartz’s story: “If you’re doing a thing you think is fine, don’t act guilty while you do it.”

At Facebook, Massachi loved working on the Civic Engagement team, which later morphed into the Civic Integrity team. Civic Engagement helped register U.S. citizens to vote and supplied election information to users around the world. “It felt like this oasis,” Massachi says. Civic Integrity was, in part, a reaction to Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election. Its initial aim was to prevent bad actors, both foreign and domestic, from using Facebook to harm the democratic process and sway elections.

Eventually, Massachi says, Civic Integrity expanded its focus to combat other abuses on all the company’s platforms, including Instagram and WhatsApp. “The team did really heroic work,” he says, even if “not all the proposals we made were allowed to be implemented.”

Massachi describes Facebook as “a big, messy place,” a mix of the good and the harmful. It always had competing priorities, he says, including “not pissing off political or media demagogic figures in various countries.”

“Donald Trump flagrantly violated Facebook rules for a long time,” he says. “It’s flagrantly unethical. The more power you have in society, the more power you have to abuse Facebook rules to get yourself more power on Facebook, which translates into more power in reality.”

Where Trump was concerned, Massachi says, “one day Facebook belatedly decided to enforce its own rules.”

It wasn’t just disillusionment that compelled Massachi’s exit from Facebook. Love also played a role. He was told he couldn’t stay on the Civic Integrity team if he moved to the Boston area, where Winsberg was relocating for her Harvard fellowship. For a few months, he worked instead for Facebook’s Presto, an open-source database engine, which he describes as “a grown-up, big-boy-pants, straight-up engineering project.”

“I really wanted to prove to myself that I could do a computer job without any tricks,” he says. “Being good at talking to people didn’t matter. It was just, ‘Can you code?’” It turned out he could. “I got a good review from my boss, and I left with my head held high.”

His LinkedIn profile says he spent the succeeding months “blissfully unemployed,” preparing for his next challenge.

No cyberutopian

In summer 2020, Massachi became a fellow (he’s now an affiliate) at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. At Facebook, he had sometimes wished for outside assistance with problems at the intersection of tech and philosophy. At Harvard, he says, his views were treated as “really cool and different and interesting,” which was “a signal that mine was a perspective that was not being heard.”

By the beginning of 2021, his ideas for the Integrity Institute were beginning to take shape.

Today, Massachi describes the Integrity Institute’s goals as threefold: “We build a community of integrity professionals. We use that community to figure out what our shared knowledge is, and then enrich and structure that knowledge and share it with the world. And we operate as an open-source integrity team that does original research.”

In October, Massachi won a 2022 Roddenberry Fellowship, named after “Star Trek” creator Gene Roddenberry and awarded to individuals who articulate “a future that is more just and fair.” He is using the $50,000 grant to help fund the Integrity Institute.

In November, he traveled to New York to try to persuade a titan of the Internet Age to donate money to the institute. The appeal “went really well,” Massachi reports, and the titan directed him to apply for funding from his foundation.

“We have big dreams,” says Massachi. “We want to have a multimillion-dollar budget.”

Hickey is among those who applaud the endeavor. “It’s a really good idea to have a think tank of professionals who engage with these issues and provide some reasoned perspective,” he says.

There is a limit to Massachi’s idealism.

“Cyber-utopians were wrong,” Massachi says. “They thought this technology was going to be a revolutionary new thing we had never seen before, which would change society in ways that were a radical break with the past. But we’re the same society with the same people and the same dynamics we’ve always had. The internet has made some things easier and some things harder. Human nature hasn’t changed.”

But that doesn’t mean integrity professionals can’t play an essential role in exploring and explaining what works online and what doesn’t. One idea, says Massachi, is to phase out or severely limit shares, retweets and message forwarding, which are “extremely powerful” tools that ideally “should be used with care.” Sharing, he says, “is how a lie gets extreme velocity before the truth can catch up” and can result in people seeing things “from sources they didn’t explicitly consent to.” Among the potential technical fixes: preventing Twitter users from retweeting retweets.

Attempting to limit online content can be problematic, he says, because it could lead to “really tricky debates about censorship.” Instead, the focus could be on online behaviors — getting rid of fake accounts and stopping spam, for instance.

Right now, Massachi says, tech platforms “incentivize doing things that are unhealthy. If you do things that are inflammatory, the algorithm and the design will reward you.” To change direction, tech employees need to be incentivized “to build systems that don’t reward the wrong behavior.”

“You could have feeds optimize on something other than pure engagement — quality, for example,” Massachi says. “You could change the rules of the platform so that spammy behavior is not tolerated.

“There are some interesting open questions,” he adds. “But we have the tools we need. There’s so much low-hanging fruit we could fix.”

From the Winter 2022 issue of Brandeis Magazine. Read the issue for more stories of trailblazing alumni.

About the Author

Julia M. Klein has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Mother Jones, Slate and other publications. Follow her on Twitter (@JuliaMKlein).