Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Alumni Reflect on the Holocaust, 80 Years Later

June 12, 2025

In honor of a solemn milestone, alumni from across the years share their personal stories and why they believe Brandeis’ founding Jewish values remain as important as ever.

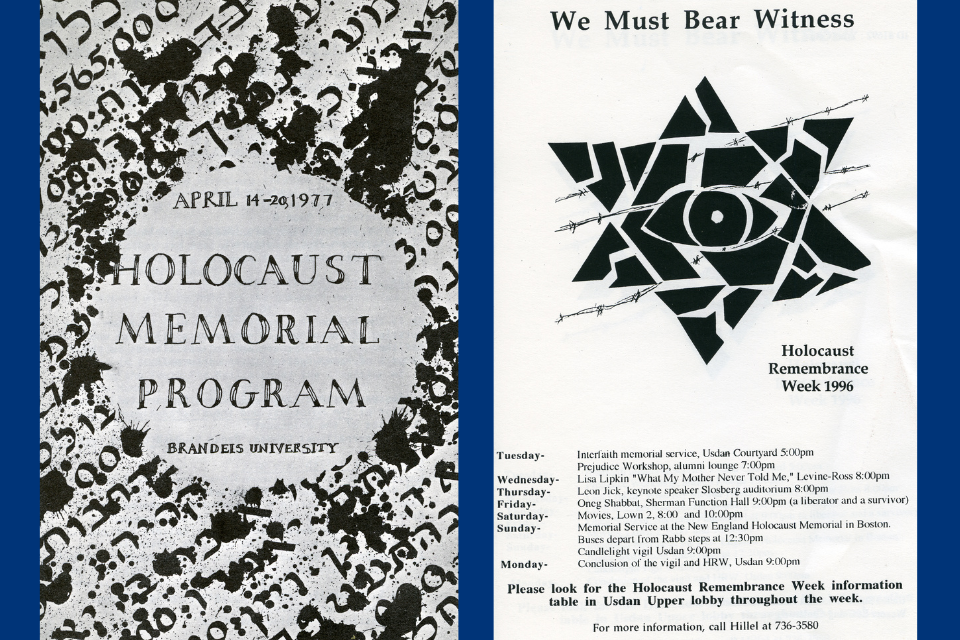

Eighty years ago last month, Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allied Forces, ending the Holocaust in Europe. Three years later, the American Jewish community founded Brandeis University as an intellectual refuge from discrimination in higher education.

Although the new university was nonsectarian, its mission was especially urgent for Jews. At the time, many other colleges and universities had enrollment quotas that limited the number of Jewish students that could be admitted. From the outset, Brandeis’ admission policies were guided by merit.

For many alumni, these two moments – the end of the Holocaust and the founding of Brandeis – are inextricably linked.

During the university’s earliest days, the vast majority of students were Jewish. Many of them also had connections to the Holocaust, whether by way of personal experience or through that of family and friends. In the years following, Brandeis continued to attract Jewish students from around the world. Among them were descendants of Jews who survived or were killed in the Holocaust, as well as many of the children and grandchildren of Brandeis alumni who shared those same connections. All the while, countless others who may not have had as direct a connection to the Holocaust were no less drawn to the university for its founding Jewish values.

But this is not just history. While 80 years have passed since the end of the Holocaust, antisemitism remains a persistent social ill. For that reason, combating antisemitism remains a university priority. In the last few years alone, Brandeis co-founded the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism; twice received the highest mark possible in the Anti-Defamation League’s annual antisemitism report card, and extended its application deadline for transfer students concerned about rising antisemitism elsewhere.

In honor of the 80th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust, alumni from across the decades shared reflections on this solemn history and why Brandeis’ mission is as important as ever.

Max Perlitsh ’52

Perlitsh was one of 107 students in Brandeis' first class.

“I vividly remember the antisemitism we faced as teenagers growing up near Boston in the 1930s and 1940s. It is the same bitter hatred that fueled the Holocaust. Many of my classmates saw their families touched by the horrors of The Holocaust. Other classmates experienced the Jewish quota system that severely restricted admissions of qualified Jewish students. In 1948, we chose Brandeis University because we knew it would always provide a safe haven for Jewish students in a world constantly ravaged by bitter Jewish hatred. Today, 77 years later, the same antisemitism of the 1930s and 40s has returned to inflame college campuses and threaten Jewish lives. Sadly, the same need for safe haven so profoundly needed in 1948 continues today.”

Helene Wingens ’85, P’14

Wingens’ parents survived the Holocaust.

“For those of us who were children of survivors, the Holocaust was never history; it was memory. And as memory, it settled deeply into the marrow of my bones. So when I arrived at Brandeis in 1981, it felt like coming home to a place where Jewish students could thrive intellectually and ethically, but more importantly to a place where I could belong. A place where my identity wasn’t something to explain or defend, but something quietly understood. What I felt immediately was the relief of being surrounded by people like me—people who had always carried a sense of otherness.”

Jonathan Sarna ’75, MA’75, H’25

Sarna is the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History and author of more than 30 books on the subject.

“America remained awash in antisemitism in the immediate aftermath of World War II. The opening of Brandeis was an important indicator of its decline. Brandeis trumpeted its merit-based ‘no quotas’ admissions policy and also welcomed Jewish faculty members, including Holocaust survivors. Many early faculty spoke with European accents and shared unforgettable stories of their European experience, which we, as students, never forgot.”

Marci Swede ’89

In memory of her parents who survived the Holocaust, Swede created the David & Lola Swede P’89 Research Fellowship for Jewish Studies.

“Even more than outright denial of the Holocaust, I am deeply concerned about its overgeneralization into a generic story on the dangers of hate. It was no accident that the Jews were targeted as scapegoats, and erasing that from the conversation disconnects the Holocaust from thousands of years of systemic Jewish persecution. Jewish studies programs provide a space for Jews to explore our history and to shine a light on the dark history of antisemitism and marginalization of the Jewish people. If Brandeis, a university founded in direct response to antisemitism in higher education, does not lead these conversations, who will? If we do not use our voice, who will speak for us?”

Alex Heckler ’98

In 2023, former President Joe Biden appointed Heckler, an attorney, entrepreneur, and philanthropic supporter of Jewish causes, to serve on the board of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“We have worked to bring elected officials from around the country to the museum, to support a robust curriculum for Holocaust education in public and private schools nationwide. What often strikes visitors is that the Holocaust story did not start abruptly in the 1940s, it began on German college campuses in the early 1930s—where antisemitism was taught and spread, almost like a virus. That history feels especially relevant today, as we witness a rise in hatred on college campuses once again. This makes the mission of institutions like Brandeis not only relevant, but essential. Brandeis plays a vital role in this moment. It has always championed social justice and the protection of all minorities, including Jewish communities

Shulamit Reinharz MA’69, PhD’77

Reinharz’ maternal grandfather died of starvation in the Gurs concentration camp; her maternal grandmother died on a train to Auschwitz; and an aunt died soon after fleeing to British Palestine. A retired Brandeis professor, Reinharz wrote the book “Hiding in Holland: A Resistance Memoir” about her father’s survival.

“Only two members of my mother’s family of five survived the Holocaust, but all five members of my father’s family survived. It’s not surprising that I grew up with constant references to my father’s experiences, but my mother was too traumatized to talk about it, except for offering my siblings and me descriptions of the many wonderful people who helped save her.”

“I wish I had gone to Brandeis as an undergrad, but for financial reasons I had to attend college closer to my home in New Jersey. There, a Jewish professor advised me to attend Brandeis for graduate school. Once at Brandeis, I found a great combination of hippie radicals and Jewish social activists. That experience kick-started my journey to finding my own way in Judaism – a journey that I love and is still ongoing.”

Detlev Suderow ’70

Growing up in Germany, Suderow says the Holocaust was rarely discussed. He learned the true nature of that history at Brandeis and converted to Judaism later in life.

“In 1966, there was virtually no one on campus who did not have a personal connection to the Holocaust. Whether it was someone in their synagogue, their community, maybe even in their own family. So here I come, this guy with a weird name and a German accent. It was intimidating, not knowing if I’d be welcome at a place like Brandeis. But I never in any way was made to feel uncomfortable. I felt comfortable the day I came to Brandeis, and I learned about that history and about Judaism here. This was the place where I grew from a parochial jock to a full-fledged human being.”

Joel Waldman ’91

Waldman’s mother is a Holocaust survivor. He recounts her story in his book, “Surviving the Survivor.”

“Fewer than 245,000 Holocaust survivors are still with us, nearly half of whom live in Israel. Sadly, this already low number shrinks smaller each and every day. It's incumbent upon Brandeis and other elite universities to double down on Holocaust education. As we all know, history repeats itself, and the unabashed antisemitism surging today is cause for serious alarm. At Brandeis, I always felt safe being a Jewish student. Today, the onus is even stronger on Brandeis to double down on Holocaust education while making sure this hideous part of our world history never repeats itself.”

Resources on Jewish Life and the Holocaust at Brandeis

Along with rich course offerings, Brandeis is home to numerous resources relating to Jewish history and life, including the Holocaust, such as:

- Published by Brandeis University Press, the Tauber Institute Series features scholarly works related to everything from the spread of antisemitism and the Holocaust to the contemporary Jewish experience.

- The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute – which serves as both incubator and launch pad for new perspectives on Jews and gender – leads research projects relating to gender and the Holocaust and hosts public events on the subject.

- The Center for German and European Studies supports interdisciplinary teaching and research on contemporary Germany and Europe at Brandeis, and hosts webinars and other events that touch on the Holocaust.

- The National Center for Jewish Film based at Brandeis holds the largest collection of Jewish film in the world, outside of Israel, with 15,000 feature films, documentaries, newsreels, home movies, and institutional films from 1903 to the present. The center, which has a rich collection of Holocaust related films, also hosts an annual film festival.

- The Judaica Collection comprises more than 200,000 works housed throughout the Brandeis Library and Archives. It documents all aspects of Jewish history, religion, and culture, with a particular focus on the Bible, rabbinics, Jewish philosophy and mysticism, Hebrew and Yiddish literature, and the Holocaust, including extensive testimony collections from the USC Shoah Foundation and Yale’s Fortunoff Video Archive.