Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Alum Uses Acoustics Expertise To Help Rebuild Notre Dame Cathedral

March 12, 2025

Brian Katz ’90 credits Brandeis with introducing him to acoustics.

In April 2019, millions around the world watched in horror as Paris’ historic Notre- Dame Cathedral caught fire and risked burning to the ground.

Built in the 12th and 13th centuries, the cathedral is considered one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture and has played an important role in French history, including hosting Napoleon’s coronation and serving as the backdrop to the novel “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.”

The church has long been known for its reverberant acoustics – the way its pipe organ, choral singing, and other sounds echo in the cavernous space. After the fire, preserving the church’s unique sonic identity was a key priority in returning the cathedral to its former glory.

Enter Brandeis alum Brian Katz ’90. The French government tapped Katz to lead a team that would restore the church’s iconic sound leading up to the church’s reopening this past December.

A concert recording makes restoration possible

Katz, who grew up in the United States and was known as Brian Gray when he was at Brandeis, is an acoustics expert at Paris’ Sorbonne University.

It was previous work he’d done at Notre-Dame that led to his involvement in the reconstruction effort. In 2013, he recorded the cathedral’s 850th anniversary concert so people everywhere could enjoy it. Using special microphones, he created an online demonstration that allowed listeners to hear how the music sounded from every corner of the cathedral.

Shortly after the fire, he started getting calls from friends asking if he had kept the acoustic measurement data and analysis from that project.

“It was serendipitous. It turned out we, [along with a few much older measurements carried out by the same lab at the Sorbonne], were the only ones who had acoustic measurements of Notre-Dame before the fire,” Katz said.

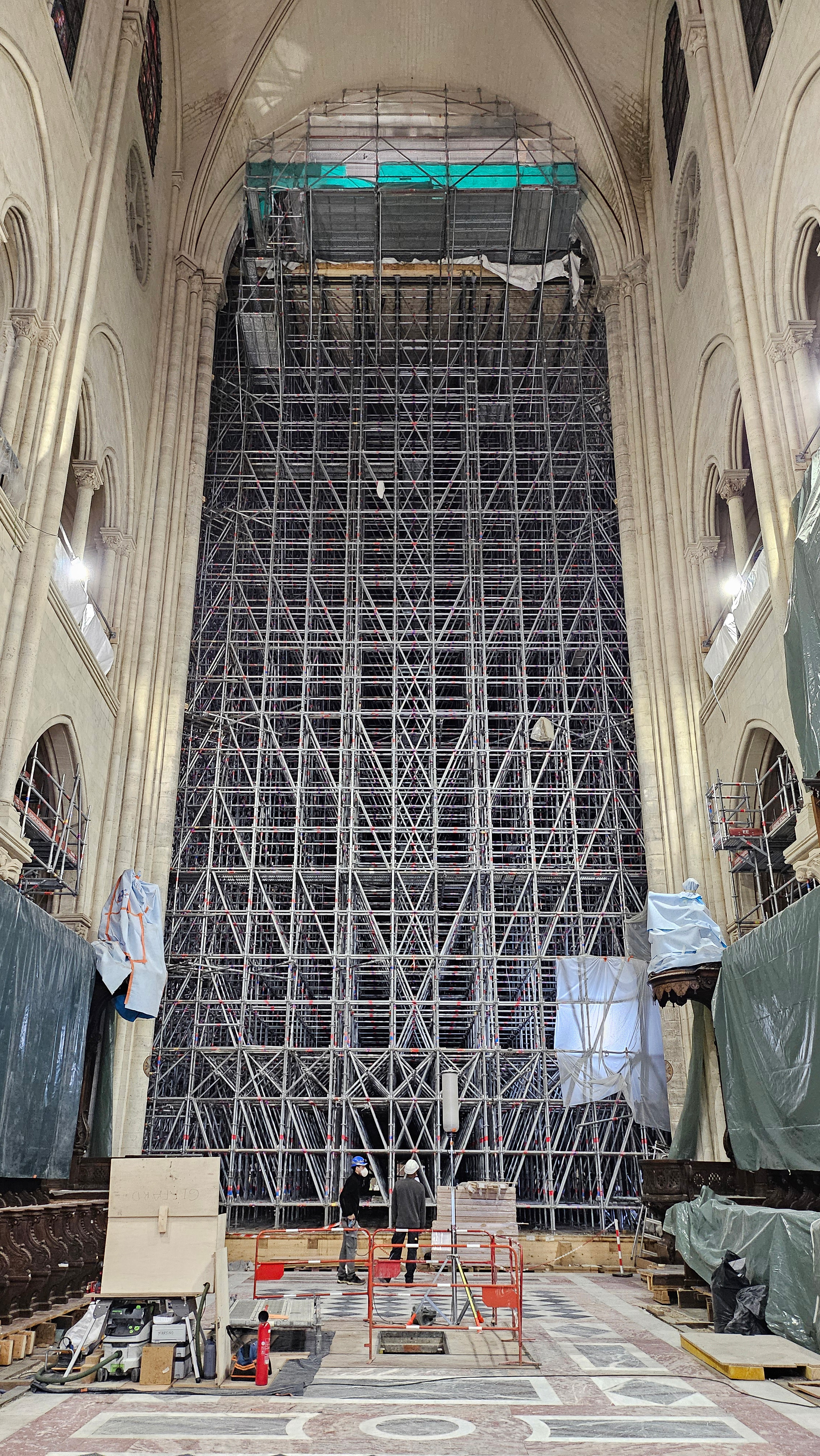

Two months after the fire, Katz’s team was finally able to safely enter the cathedral. Piles of rubble lined the floor, and holes in the ceiling raised fears that the roof could still collapse. For safety reasons, he and his team had to use a robot to collect data in more treacherous spots.

“It was surreal. Typically, Notre-Dame is packed with worshipers and tourists. We were alone in the cathedral for hours wearing masks and hazmat suits,” he said. “You could still smell the burnt wood. I’ll never forget it.”

Katz and his team got to work comparing pre-fire data against new measurements they collected after the destruction. From there, they worked with state authorities to make sure rebuilding decisions were made with sound restoration in mind.

The team was also charged with educating the public about the history of sound at the cathedral and how it had developed over centuries. Toward that end, they launched a radio show featuring historically accurate recordings and developed an audio guide for visitors.

His work’s not done yet. He will soon take the first post-restoration acoustic measurements of the church in order to assess whether additional work is needed to restore its original sound.

Finding his passion at Brandeis

Katz knew nothing about acoustics when he arrived at Brandeis, where he double majored in physics and philosophy. But one fateful day, a senior on his dorm floor tapped him to manage sound for the student group that hosted campus dances, parties, and other events.

“I didn’t always like the music played at events, but I was fascinated by the technical side,” he said.

Ironically, he only took French to fulfill a core requirement, and he barely passed.

“At the time, I didn’t see the point of learning French – I would never use it,’” said Katz, who is now a dual citizen of France and the United States. “The fact that I’m living in France, speaking French every day, showcases how you never know what’s going to happen.”

After graduating, he went on to earn a PhD in acoustics at Penn State. He worked for a while designing concert venues – covering everything from the shape of the room to the placement of furniture and speakers – to give the space optimal sound. In 2001, he moved to France on a cultural exchange grant to study acoustics.

“I got my start in building sound systems at Brandeis. I’ve carried that work on campus with me ever since,” he said.