Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

How One Alumna Stumbled on a Life-Changing Secret

Genetic testing reveals a 50-year-old secret — and enlarges one woman’s sense of family.

A few years ago, out of curiosity, I sent a DNA sample to 23andMe. I knew my dad was an Ashkenazi Jew, but I wanted to know the percentage of Italian ancestry on my mom’s side.

Months later, my whimsical endeavor became dramatically less whimsical. A truth bomb, in the form of an email from a guy in Florida, detonated on-screen: “23andMe says you’re my half sister,” wrote Nick (not his real name). “I’m very confused. Can you call me?”

Nick, a year younger than I am, looked like my long-lost twin. During our first phone conversation, we learned we’d grown up a 30-minute drive apart, near New Haven, Connecticut. We quickly theorized my dad must have had an affair with his mom.

Within the space of a few hours, though, several old-timers in our families had corrected us. Our fathers had been infertile. Nick and I were conceived from donor sperm — clearly, the same donor’s sperm. In the commercial DNA-testing world, such a surprise is known as an “NPE”: “not parent expected” or “nonpaternity event.”

My NPE felt destabilizing, yet I was also exhilarated. I was an only child who suddenly had a sibling. I was an orphan who might have another parent figure somewhere out there.

It was like Nick and I had been in a car crash and we sat stunned in the smoking vehicles that had once been our perfectly coherent life stories. Our connection quickly became intimate — not surprising, considering it began with a discussion of the sperm that entered our mothers’ uteruses 50 years earlier.

The day after our revelation, Nick went on a mission to find our sperm donor, whom we began referring to as Our Guy. After 10 weeks of genetic sleuthing through a line of second cousins listed on the 23andMe site, Nick found a likely prospect. Even a sideways glance at his photo confirmed this was indeed Our Guy. The three of us shared the same dimple on our nose tip, the same deep-set blue eyes, even the same wrinkle patterns.

Better yet, Our Guy was still alive. His name was Frank. He was a 79-year-old retired obstetrician living in Nashville, Tennessee. He’d raised three kids. And, like my dad, he was an Ashkenazi Jew.

In the late 1960s, the sperm that created Nick and me came from a new sperm-donation program at Yale New Haven Hospital’s infertility clinic. OB/GYN medical residents were paid $25 for each “fresh sample” they donated, and there was always one donor available per shift. There likely would have been no way for my parents or Nick’s parents to choose which donor they got.

Nick and I decided to get in touch with Our Guy. We labored over our letters, trying to convey the respect and gratefulness that swelled within us in a way that felt almost holy. “I realize this is likely not the future that you or anyone foresaw a half-century ago,” I wrote. “But here we are, for better or for worse — hopefully for better — with easy access to DNA tests. And now my reflection in the mirror is different from the one I’d seen before. Connecting with you, expressing my gratitude, asking you a few questions and receiving answers would be a very important moment in my life, a life I am thankful for every day.”

As I waited in agony for Frank’s response, a few well-meaning friends and family suggested I focus on how lucky I was to be alive and to have had such loving parents. “It’s just sperm” and “You were so wanted” are common (and often annoying) refrains donor-conceived people hear.

I did feel deeply lucky. At the same time, I felt a primitive yearning to lay eyes on this man and, in turn, be seen by him. He was the reason I was here. I was “of his flesh.” That made him of great relevance to me.

But Frank held all the cards. In the Facebook group We Are Donor Conceived, which Nick and I had joined, I read about the disappointment and devastation caused when sperm or egg donors ignore or reject communication from the children they’d created. Some donors respond by saying, “No contact, please,” “That was a long time ago,” “I was assured anonymity” or “My family isn’t comfortable with this.” Some even send cease-and-desist letters.

Happily, Our Guy did none of this. Three weeks later, in a thoughtfully composed letter brimming with empathy, he told me he was open to more communication. During our first phone conversation, he seemed proud the DNA passed to him by his parents was passed down to me with seemingly positive results. He was glad his sperm sample had led to my parents and me having happy lives together.

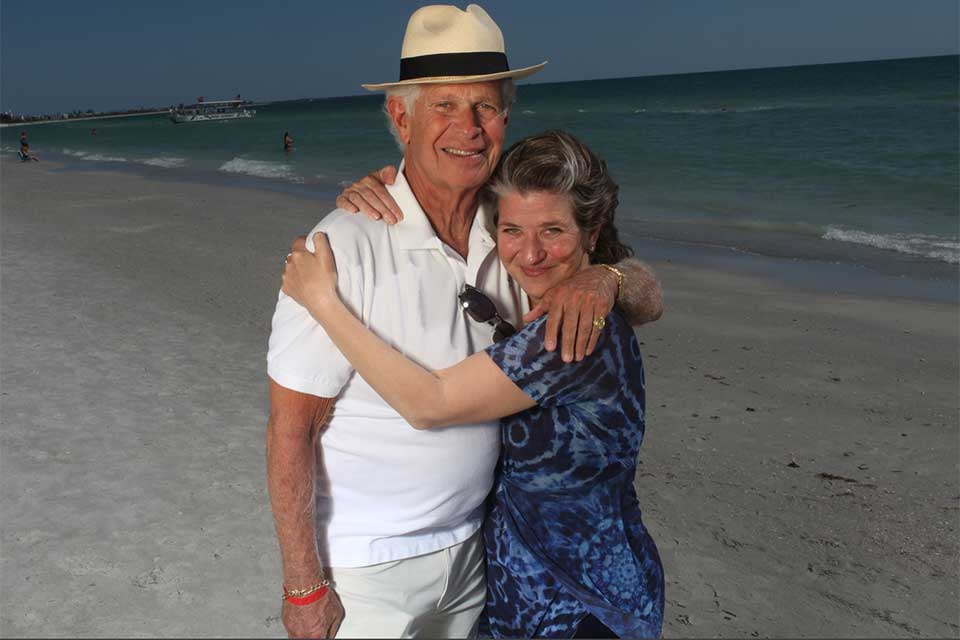

Since then, I’ve had many visits and video chats with my new “bamily” (short for “bonus family”). My bamily includes Frank and his wife, Julie; four half siblings and their spouses; and 11 nieces and nephews.

When I look at those who share my gene pool, I see so much of myself, and so does Frank. Recently, he wrote:

You and I not only have very similar physical traits, but also similar personalities, interests and lifestyles. Nature loads the gun, and nurture pulls the trigger. My only contribution so far has been loading the gun. Despite no nurturing on my part, you and I are both quite outgoing and gregarious, love to exercise, and have chronic mild anxiety. We both love swimming and bird watching, and both of us have homes on the ocean, a place that brings us much peace and comfort. It seems that nature is more dominant in who we become than was once thought.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Kama Einhorn

Nick’s and my story started with negativity — the painful “no” of infertility. But since then, there has been so much “yes.” More than 50 years ago, scientists said yes to pioneering a controversial new procedure, intrauterine insemination. At age 28, Frank said yes to donating his sperm. My loving parents — both my mother and my macho dad — said yes to insemination. Nick and I said yes to genetic testing, and to finding and contacting our biological father.

Finally, of course, Frank’s response to Nick and me was a loud yes. He met with us in person. We communicate frequently. His wife and their children opened their arms to us. He wrote me, “We continue to say yes to building new relationships within this uncharted territory, for which there are no guidebooks or road maps. The word ‘yes’ has become a very important word in our family vocabulary.”

Frank has admitted that, when we first contacted him, he was hesitant to respond, wanting to avoid opening a complicated can of worms. But Julie told him, “Frank, this isn’t about you. You know who you are. It’s about them — they don’t know where they came from, and they have a big hole in their lives now.”

Issues around assisted reproductive technology are not black-and-white. Many donors and recipient parents have good reasons for wanting to keep this uncomfortably personal transaction anonymous, simple, clean. But donor-anonymity agreements — which are still common — require something unusual of the eventual offspring. At the time the contract is signed, we are not even fetuses; we are wishes, theoretical beings. We are not parties to the contract, though it’s the foundation of our existence. If we can’t find or are rejected by our donor, we are forced to honor a contract we did not sign.

Anonymous sperm or egg donation is a story of “no.” I’ve come to believe it violates a basic human right, the ability to connect to one’s life source. Fortunately for Nick and me, Frank let himself be known, and he made sure we felt seen and heard by him. “Thanks for finding me,” he wrote me recently. “You have enriched my life and the lives of my entire family.”

My bamily’s story is about showing up and revealing ourselves, not crouching in the darkness of old secrets. The world needs good stories these days, and we all need a little renewal of faith. We need to marvel at the life force, which so often finds a way forward despite challenges. We need to say hineni (Hebrew for “here I am”). We need to bask in the good intentions of others. We need to say yes more often.

From the Summer 2022 issue of Brandeis Magazine. Read the issue for more fascinating alumni stories and perspectives.

About the Author

Brooklyn resident Kama Einhorn is an Emmy Award-winning “Sesame Street” writer and the author of a young-reader series of books about animal sanctuaries. She has the word hineni, written in Hebrew, tattooed on her ankle.