Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Famed Bassist Chuck Israels ’59 Surveys Jazz Landscape, Then and Now

At work on a memoir, the Grammy-winning musician, composer and educator reflects on his Brandeis days, when he landed a gig with Billie Holiday, and his long career sharing the stage with icons including Bill Evans, John Coltrane and Nina Simone.

Chuck Israels’ long and luminous professional jazz career got its jump-start when, as a Brandeis student, he was hired to accompany the legendary singer Billie Holiday. From that day on, Israels and his bass have shared the stage with a parade of jazz icons from his days touring with the Bill Evans trio to his Chuck Israels Jazz Orchestra in his home of Portland, Oregon. Scores of albums, a Grammy and a long teaching career later, at the age of 85, Israels is at work on a book about his life, his music and the provocative insights and views gained as a tireless promoter of jazz in a changing world.

An MIT dropout who realized, as one journalist later put it, that he was better suited to EE (Ellington and Evans) than to EE (electrical engineering), Israels transferred to Brandeis with a recommendation letter from Eleanor Roosevelt. Brandeis proved a far better fit for Israels. He grew up in a house full of books and music; his activist stepfather, a professional singer, counted fellow artist-activists Paul Robeson (godfather to Israels’ brother) and Pete Seeger among his close friends.

Israels had his first professional recording session as a Brandeis student. It was a dazzling debut: “Coltrane Time” is the only recording of the legendary saxophonist John Coltrane and avant garde pianist Cecil Taylor. With Israels on bass, the ensemble recorded one of Israels’ compositions, a homework assignment titled “Double Clutching.”

“Most people will never hear jazz. It’s hard to find on the radio and very few venues offer it. Unlike pop music, which you can’t avoid, You don’t generally bump into jazz by accident in your daily travels. You have to seek it out.” — Bob Nieske, jazz bassist and Brandeis Professor of the Practice (Jazz)

After a postgraduate year bouncing around Europe, Israels became the bassist for Evans and joined the masterly pianist’s trio for a six-year stint that included a memorable UK tour. Bob Nieske, jazz bassist and Brandeis Professor of the Practice (Jazz), counts Israels’ work with the trio among his favorite Evans recordings. “Chuck and drummer Larry (Bunker) are so clear and direct in the time (without being tight) that it allows — forces? — Bill to take his time and swing,” said Nieske. “Chuck has a way of breaking up the time or floating over it while still being very clear and coming home to roost.”

Nieske also praised Israel’s writing and playing with the Metropole Orchestra in the nineties, a blending of classical orchestration and jazz. “It’s very difficult to get a classical orchestra to swing and Chuck solves that problem by not asking the strings to swing with the rhythm section very often,” said Nieske. “He uses them in a way that highlights their strengths, which is the mark of a terrific composer.”

Israels has played with a who’s who of musical giants including Benny Goodman, Stan Getz, JJ Johnson, Herbie Hancock, George Russell, Coleman Hawkins, Nina Simone, Barry Harris, Eric Dolphy, Rosemary Clooney and Barbra Streisand. A strong believer in jazz education, he has taught at the New England Conservatory of Music, Juilliard Conservatory, Eastman School of Music, Brooklyn College, Koln Conservatory, the conservatory in Graz, and, for 24 years until his retirement, he headed the jazz department of Western Washington University.

The Brandeis Alumni Association spoke with Israels recently via Zoom while his wife — the widely recorded jazz, Broadway and opera singer Margot Hanson — practiced her flute in the background.

How has jazz evolved since your early days with Bill Evans?

Let me paint a cultural picture. At the end of the 1960s, 76 million baby boomers reached adolescence — teenagers who had money in their pockets. I grew up in circumstances where popular music was written and consumed by educated people; that shifted to the more normal circumstances of today where popular music is written and consumed by the musically uneducated. The catalyst that stopped this wonderful era from the late 19th to the mid-20th century was young people who had money so the market gravitated there, to undeveloped adolescent sensibilities. That marginalized Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Bill Evans, Thelonius Monk.

You were admitted to Brandeis with a boost from Eleanor Roosevelt. What was your connection to her?

My paternal grandmother was Belle Moskowitz, the prominent political influencer and campaign manager to New York Governor and 1928 presidential candidate Al Smith. She was close with Roosevelt, (a Brandeis trustee (1949-62), and honorary degree recipient.) When Phil Driscoll, this really lovely admissions officer, took me on as a project, he said it was well past the admissions deadline and we had to make a pressure case. “Who do you know?” he asked. My father, who divorced my mother when I was four, somehow came through for me by using this connection. By doing that he allowed me to stay in school and kept me out of the army during the Korean War. I was terrified of the military. I guess I was one of those privileged kids whose parents manipulated the system in my favor.

What was your jazz education like at Brandeis?

I’m grateful for many things that Brandeis provided me, foremost the fact that it allowed me to stay in college after I flunked out of MIT. I’m grateful for the education I received, and the chance to study with teachers like Harold Shapero, Max Lerner and Abe Maslow. People knew me on campus as the jazz guy. Looking back I see that this was my identity, the only way I was going to get anyone’s attention. But I want to make an important point: There’s a built-in institutional negligence of jazz at many institutions of higher learning, Brandeis included. It’s an enormous oversight and misunderstanding of American cultural history.

What was that moment?

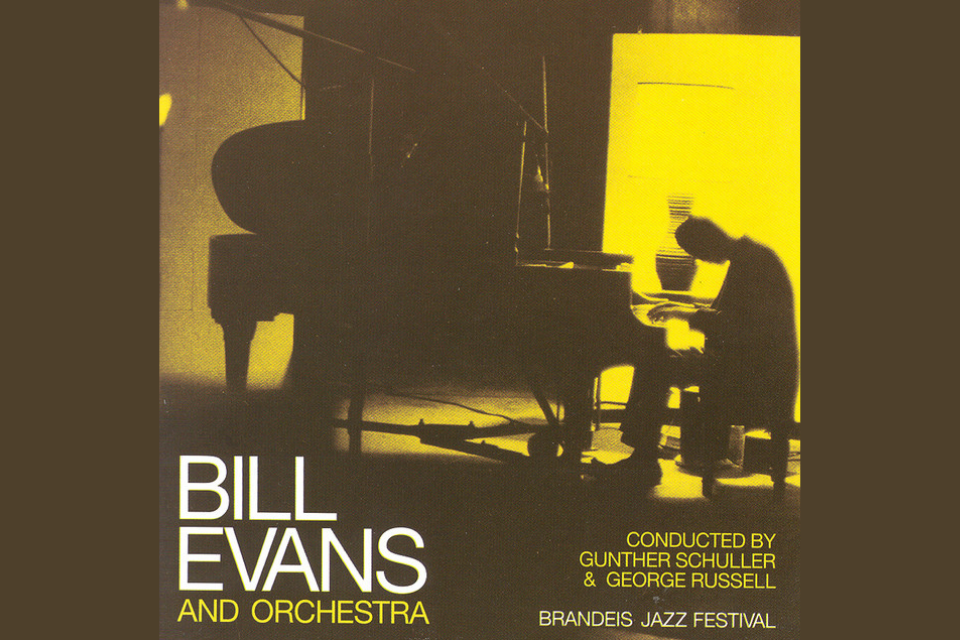

The 1957 Brandeis Jazz Festival. Immortalized in a live recording, it was pivotal in my growth as a jazz musician. That was when jazz was elevated in stature by composer and Brandeis lecturer Gunther Schuller, co-founder of the American Jazz Society, and the people who were running the music festival that June. Schuller, who coined the term “third stream music,” was hired to run part of the jazz festival and to write and commission music for a group of virtuoso jazz musicians who came from New York and rehearsed on campus for about a week. All those people became my friends. As positive as that was, and as much as Brandeis was responsible for it, it would never have happened without the contrived presentation of these people’s music as it related to European classical music. If their music hadn’t been considered “third stream,” Charles Mingus, Bill Evans, Art Farmer and Joe Benjamin wouldn’t have been there.

How did you land a gig with Billie Holiday?

I was 22 and spending the summer in Stockbridge [Massachusetts] when Phil and Stephanie Barber — owners of Music Inn — produced a concert with Billie at the Music Barn. Billie came with her pianist, Mal Waldron, and I was hired to bring a drummer (Jimmy Zitano, from Boston). I was so preoccupied with doing my job, I hardly remember much about how Billie sounded. I do remember that she let the audience know that she was satisfied with the accompaniment she got from two musicians who’d been strangers to her until the short rehearsal before the performance.

Your jazz education outside of Brandeis — where did it happen?

My jazz life took place in Boston and Cambridge. There was a guy named Tom Wilson. We became really close and I spent many days skipping school and hanging out with him at the record company he ran from his home in Cambridge and at the Jazz Workshop on Huntington Ave. That place is now the air above the Mass Pike.

When you left Brandeis were you already deep into the jazz world?

After graduating I did what people did in those years: I went to Europe to find myself. I had a thousand dollars which was a lot of money then. We went to Europe to get away from our parents, from our normal surroundings; that was a ritual of the time for a lot of people in my socioeconomic group. My music was pretty much established when I went to Europe. My general level of ability and musicianship was good, I had a pretty good foundation from Boston. I did get work with (American jazz pianist) Bud Powell in Paris.

After your version of the Grand Tour, how did you launch your music career in the U.S.?

I was in Europe for 9 or 10 months. When I came back, Club 47 (now Passim), where I’d played in college, had changed from a jazz venue to a folk music club, and people like Joan Baez were performing there. But a few months later, jazz composer George Russell, who I met during the Brandeis Jazz Festival, hired me to join his sextet, which was scheduled to play at the Five Spot in New York.

What did being part of a thriving jazz community mean to you?

I was so satisfied with being able to play the bass, and being part of that community, and to be accepted by a society of musical democracy and equality. Another big effect was the sensual part of it, it feels in my body like American music. It flows through my ears and into my muscles and legs. No other music feels that way to me as much as I love and respect Mozart and Schubert and Bizet, the list goes on. Some come close; I sure get wrapped up in “Carmen.” But there’s something about the rhythmic language of jazz, the combination of tension and resolution of West African and European sounds that is completely American. It only happened here and in an uncontrived way. It’s the real fusion, and it happened by proximity.

What was your greatest musical experience?

Certainly playing with Bill (Evans). I don’t think I’ve matched the pleasure of that. There was something just so sensual in the way this guy played; it was a real connection. It just enveloped you. Making music like that is one of those experiences that when you’re in it you don’t think about dying; you’re immortal. You feel the absolute power of the present moment and that makes it feel so compelling and so addictive. And it was at a time in Bill’s career when we could do that night after night after night. If you go on YouTube and look at us in 1965 in London, it looks so perfectly executed because we were doing it every day.

How did jazz shape your values?

We’re in a difficult time culturally. I lived through the McCarthy era, and today it’s been five or six years of similar political chaos and I don’t have the answers. I only know that again and again I come back to the fact that the marginalization of jazz left a hole in our culture that parallels the hole in our politics. “Turn on, Tune in, Drop Out” was the music of the era. What jazz was, was a real model of inclusion, diversity and equality. It gave us a democratically-led model of diversity and inclusion — not just rhetoric. It’s the model for God’s sake and at least we ought to understand it culturally and politically. I think about this all the time.

It’s not uncommon for people to declare that they “hate jazz.” How would you respond to them?

If you have no education in it you’re not going to like it. I’m 85 and I’ve thought a lot about this: There’s no art form more abstract than music. It’s just an assembly of sequences of sound that does something to us as human beings. What is this mysterious thing that it does? So many things are opened up in this question. We appreciate languages we understand. Music is a variety of languages, not a universal one, despite being advertised as that. Chinese or Balinese music doesn’t affect me the same way jazz does because I am educated in jazz music. If you don’t have that education it may strike you as off-putting. Perhaps jazz is too sophisticated. People have been dumbed down by mechanical drum beats and by what you see if you watch late night TV shows — at the end they have some music and it’s God-awful. It doesn’t relate to my experience as a human being,

Do you think jazz has had its heyday?

Jazz doesn’t live the way it used to. We’ve lost a lot, culturally and politically, and these are intertwined. Do I think the human spirit is crushed and nothing new as artistically important as jazz will arise? No, I don’t think so. I think this particular, fortunate golden era of high-level popular music, which was particularly American, is done, and I was bloody lucky to have lived in it.

About the Author

Former senior editor of Bostonia, Susan Seligson is an award-winning journalist who has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, The Times of London, Redbook, Yankee, Salon, The Boston Globe, Radcliffe Magazine and many other publications. She is the author of several books including Going with the Grain (Simon & Schuster).

Published On: August 23, 2021