Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Artist Natasha Frye ’14 Channels Wampanoag Roots with Bold, Blazing Works

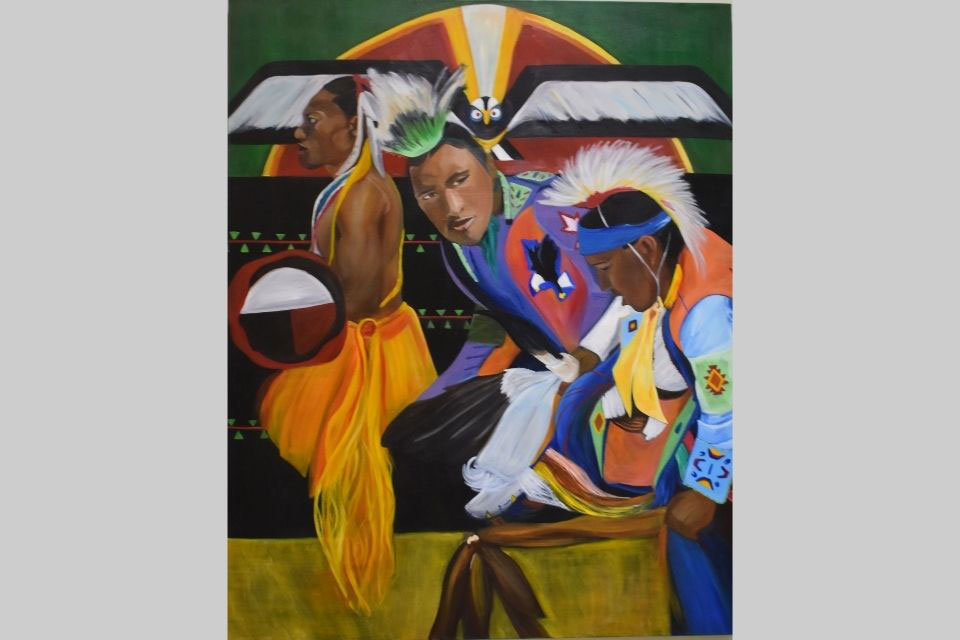

Full of tribal symbolism and fueled by memories of powwows past, Frye’s colorful paintings adorn a Wampanoag trading post and gathering space in her native Mashpee, Massachusetts.

It took three decades of tireless advocacy, but in June 2016 the Organization of American States adopted the landmark American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples. In each of the 35 member states of the Americas, indigenous peoples are ensured the right to self-government, education, culture, lands and natural resources. For Natasha Frye ’14, who is part Wampanoag and has settled in her birthplace and tribal home of Mashpee, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, the story of her people continues to unfold in the wake of these long-overdue resolutions. As her role in the tribe grows, Frye, a visual artist, tells the story of the Wampanoag in expansive colorful canvases that double as memory paintings for her personal experience and that of her ancestors. Like the powwows and tribal lore they reflect, the richly detailed works are declarations in and of themselves: The Wampanoag were here centuries before the arrival of Europeans, and they are here today, actively steeped in community traditions.

In a walk-through of the Wampanoag Trading Post and Gallery and a nearby art and gathering space in Mashpee Commons, Frye uses her many works on display as a guide to her development as an artist informed by her Wampanoag identity. An early painting called “Drumbeat” was influenced by the drumming at the powwows she began attending as a child. “Early on I was painting a lot of colorful shapes and wasn’t sure where they were coming from,” says Frye, who runs children’s art workshops for the tribe. “My paintings weren’t about the Native American experience at first,” she said. But works to follow explored that experience in detail. Each song and dance carries a different meaning, each piece of regalia — headbands, leggings and bells — has its own significance, she explains.

As Frye’s paintings incorporated more and more tribal symbolism, she began adding texture in the form of crushed wampum — rose-tinted shards from the shells of local quahogs. The wampum she uses carries special meaning; it was gathered with her family on summer clamming outings.

Frye recalls that she was encouraged to “work big and bold” while a student at Brandeis, where she was in the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program. Brandeis Fine Arts Professors Joe Wardwell, Graham Campbell and Susan Lichtman had a great influence on her, she says. “They helped me find my artistic voice and develop my way with painting and subject interests. I still paint with all they instilled in me.”

Who Are the Wampanoag?

Frye is accustomed to people’s lack of knowledge about the Wampanoag tribe, also known as “People of the First Light.” “If you’re not from the Cape you probably haven’t heard of us,” she says. But the Wampanoag figure strongly into the debunking of the simplistic, flawed narrative of America’s “discovery” by Europeans in the 15th century. Populating parts of Cape Cod and eastern Rhode Island dating back 12,000 years, they were the first tribe encountered by the Pilgrims when they landed on the Cape tip (now Provincetown) and moved on to Patuxet (now Plymouth) in 1620.

In spite of these deep roots, the tribe was only officially recognized at the federal level in 1987. It now holds 321 acres of land in trust, and operates as a fully sovereign nation, with its own police department, housing development projects and Wampanoag-language elementary school.

At an unnamed cavernous space not far from the Trading Post, Frye’s paintings dominate the walls. She finds it thrilling that these works, here indefinitely, are what people see when they gather for tribal meetings or when tribe members greet visitors or locals wanting to learn more about the Wampanoag. Here, the tribal elders, including the esteemed clan leader known as Mother Bear, hold dinners, public talks and arts programs, including an after-school program Frye oversees. “I love just being within the Wampanoag community and doing something special with the kids, as well as exploring and sharing my work and techniques,” says Frye, who has her own workspace here. “With any tribe there’s so much art involved, the beadwork, the regalia — it’s another outlet for the kids.”

Art Infused with Culture

Frye has been drawing and painting her whole life, a fact underscored enthusiastically by her mother Lynette Perdiz, who moved to the Cape from New York City to raise her children close to the tribe. At Brandeis, Frye was nudged toward working in oils, and the brightly colored narrative works took shape. “By the time I was graduating, I realized that growing up on the Cape with the Wampanoag tribe was always on my mind, and my art was an outlet,” says Frye, who has also created murals. Infused by a range of influences including Henri Matisse and Frida Kahlo, the paintings sometimes depict actual tribal elders or historic figures. The square canvases are full of sweeping motion and juxtaposed patterns. Some of the patterns are imported from Native American imagery, but most were reimagined by Frye. The more you look, the more you see: plants, animals, human faces, drums, feathers, stars, water, fire.

One of Frye’s most intriguing paintings was inspired by the post-powwow tradition known as Fireball, a healing ceremony. According to a description on Capecod.com, volunteers honor their sick or ailing loved ones with the ceremony which can appear to be “similar to soccer with a flaming ball.” The Wampanoag call the fireballs, which have been pre-soaked in kerosene, “the light of life.” In Frye’s painting, the fire explodes onto a dark background.

Though Frye describes many of her paintings as “purposeful,” other times “things just happen,” she says. While she loves selling her paintings and knowing others are enjoying them, she’s in no rush to part with them. Gazing at the walls as visitors stream in and out, Frye says to herself, “I can’t believe I painted all these.”

Looking to connect with fellow alumni in the arts? Learn more about the Arts Alumni Network.

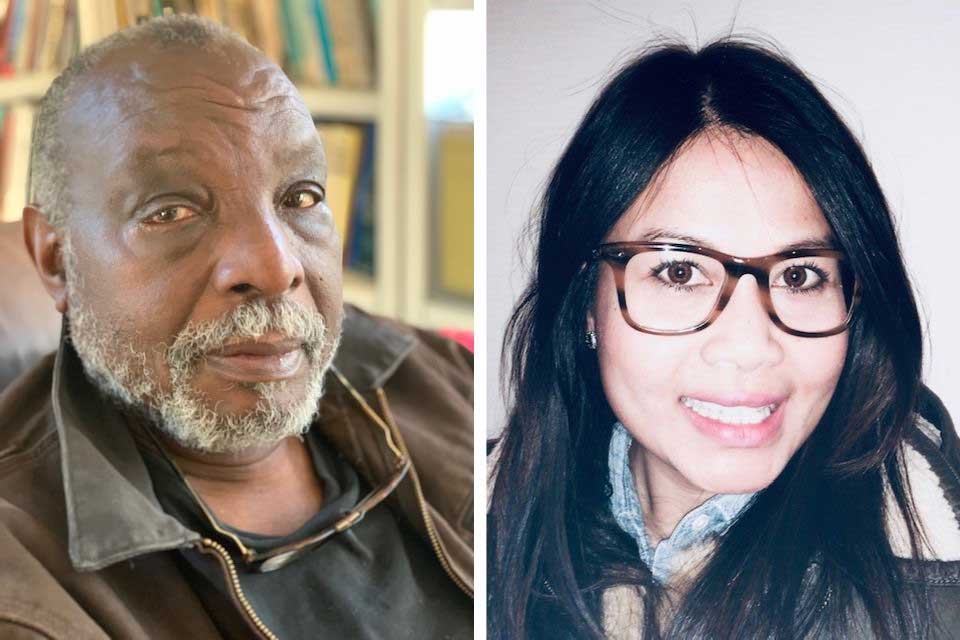

About the Author

Former senior editor of Bostonia, Susan Seligson is an award-winning journalist who has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, The Times of London, Redbook, Yankee, Salon, The Boston Globe, Radcliffe Magazine and many other publications. She is the author of several books including Going with the Grain (Simon & Schuster).