Brandeis Alumni, Family and Friends

Creator of ‘Invisibility Cloak’ Advocates for Ethical Invention

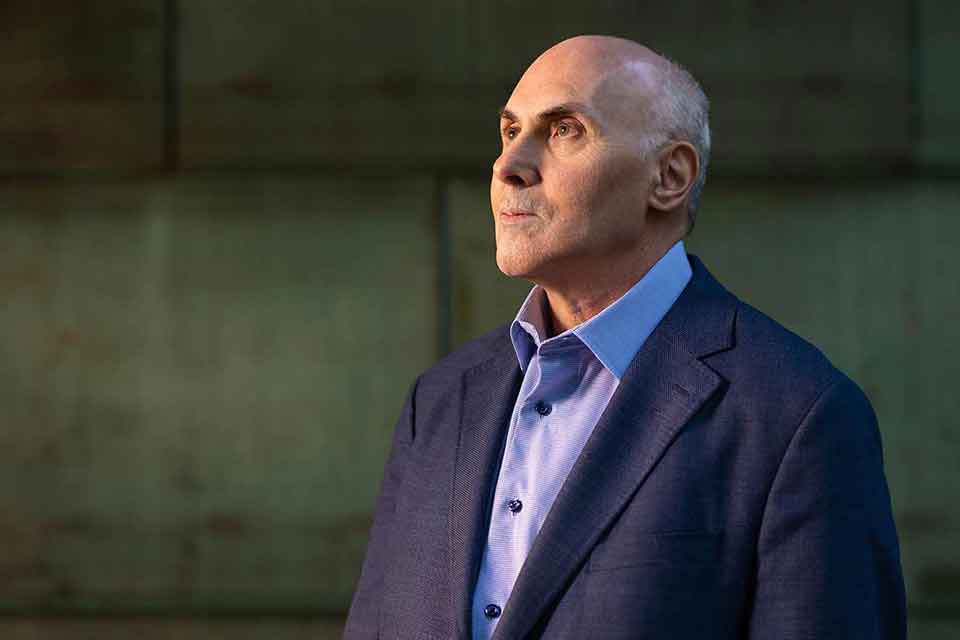

Faced with a moral dilemma, Nathan Cohen ’77 created new technology to negate one of his own inventions.

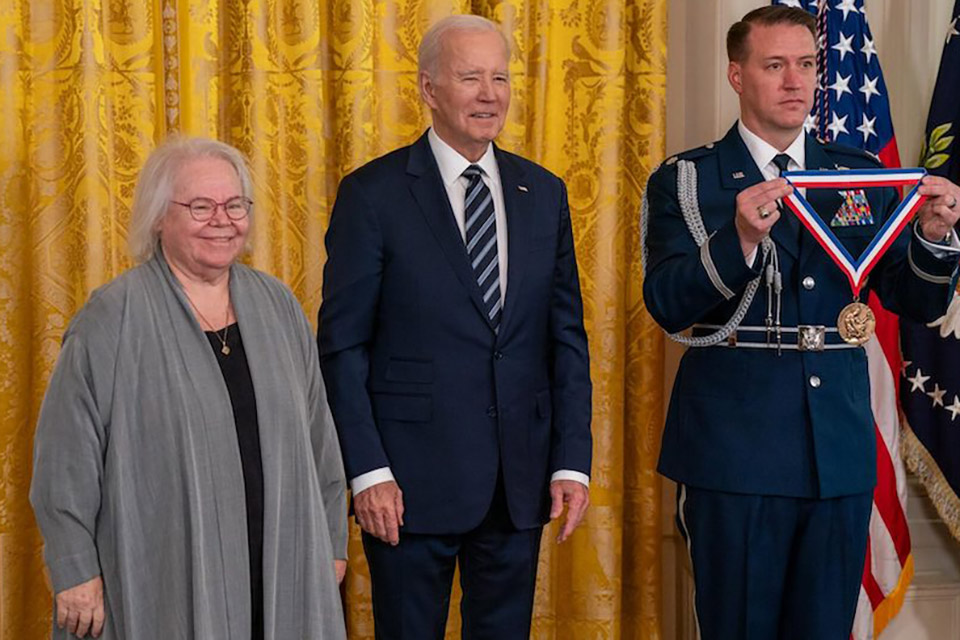

Photo Credit: Courtesy Fractal Antenna Systems.Inc.

In 2003, Nathan “Chip” Cohen ’77 invented the invisibility cloak.

No, really! He patented and demonstrated technology that could effectively hide structures and objects from radar detection by redirecting their electromagnetic signals.

The invention – which might seem like something out of a sci-fi thriller or a Harry Potter book – excited him from a scientific standpoint as a former physics major. Yet he struggled to imagine the real-world applications, and how it could be used for good. Worse, he could easily imagine how such technology might be used to harm.

He started to wonder, ‘What am I going to do with it?’” he says. “What do we really need to make invisible? I could envision bad actors using cloaks to make people, or tanks, or rockets invisible. I wasn’t happy about that at all and I didn’t want to be the person that enabled that.”

Faced with that moral dilemma, Cohen says he decided to sit on the technology, but then researchers elsewhere began to close in on their own cloaking methodologies. That inspired him to come up with a way to counteract and negate his own invention. And in 2022, his company, Fractal Antenna Systems, Inc. announced it had secured a patent on a method to detect invisibility cloaks, “thus preventing hostile military assets from being hidden from radar and decreasing the potential for sparking conflicts.”

“I had to draw a line in the sand and take responsibility,” he explains.

With the rise of AI worrying many, we caught up with Cohen – who has a distinguished career as a professor and radio astronomer, and is currently an entrepreneur and lead inventor (with 93 U.S. patents) at his company, Fractal Antenna Systems – to discuss the ethical dilemmas inherent in the act of invention.

When you have an idea, do you worry about whether the possibly good applications of it outweigh its dangerous applications or vice versa?

Of course I worry about it! In fact, it’s my overriding concern. The problem is, and this really bothers me, that many scientists and inventors don’t feel they need to take responsibility for how their creations are used. Someone else can come up with a way to stop it.” I start with the premise: “How does this enhance the human condition?” and then ask: how can this be abused?” I can suggest two very recent examples where other innovators dealt with this moral dilemma.

What are they?

Elon Musk is an obvious one. He turned off Starlink (an internet service operated by Musk’s company SpaceX) in Ukraine to prevent what he perceived as the possibility of World War III. He certainly is aware of how his technology might be used.

Robert Oppenheimer’s involvement with the atomic bomb was brought back to the forefront by the recent blockbuster movie. Clearly, many physicists were extremely unhappy with what they discovered they could do. They made it extremely public and the outcome of that is the so-called the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, dedicated to preventing the use of nuclear weapons.

Can ethical quandaries deter inventors from pursuing ideas or stifle innovation?

I have seen very few examples where inventors and innovators take the time to find out how their innovations and inventions could be abused. And I think the reason for that is not because they’re immoral or unethical people. I think it’s because it’s not embedded in the process of invention. It’s outside of their realm of experience, and they’ve never been educated about its importance or how to do it.

We still have this attitude of, “Oh, let’s put on a show and have fun.” That’s great, creating something and then going to Kickstarter or elsewhere to raise money, start a company, and produce a product. But you better understand what you’re doing and the possible ramifications. I think we have an obligation to teach inventors. Who does the teaching? A school’s philosophy department? Maybe. A business school? Maybe. I think certainly there’s a better sense now of pursuing ethical and moral issues within the business context than there has been in prior years. But we need students to review case studies and learn examples of what can happen when people don't think these things through. When they have that education and understanding, they’ll be more likely to consider the implications of their work.

How did your time at Brandeis help you in your career or help to set your ethical compass as an inventor?

An advantage of Brandeis is its moral culture, and the opportunity for exposure to it while being scholarly, even as a scientist. No one is forcing you to understand social issues or to understand the liberal arts if you’re a scientist. But, at Brandeis, it’s hard to not be exposed to it, and that’s an amazing life lesson.

I had the advantage of being at Brandeis, where I was confronted daily with these issues of: “How does this affect other people?” Physics was not at that time considered a cool major at Brandeis. I wanted to be at Brandeis because it was a place where I could gain exposure to other points of view. I sure wanted to understand other points of view, whether I agreed with them or not, and Brandeis is a place where that opportunity exists.

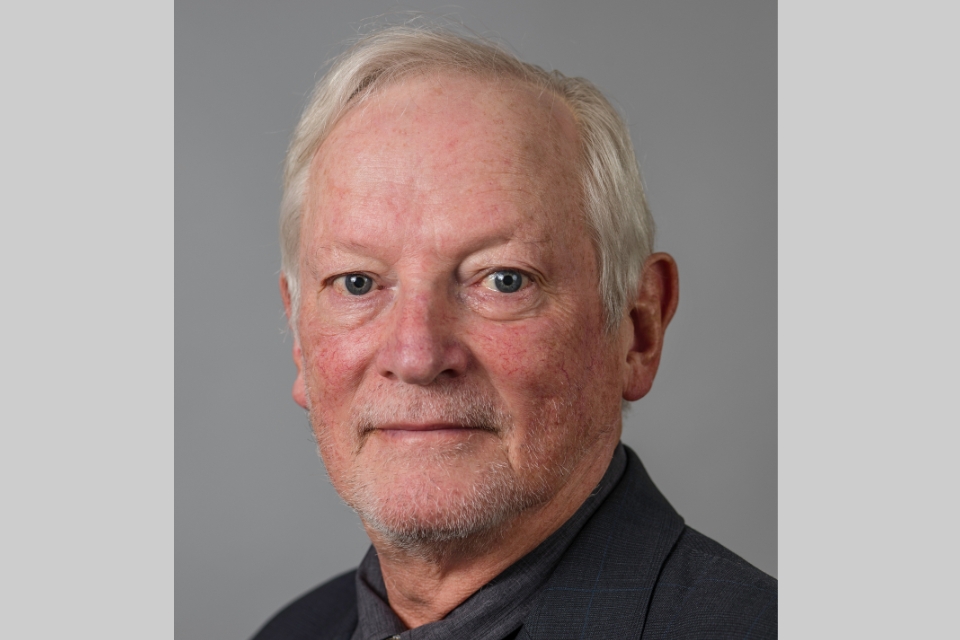

– David Eisenberg